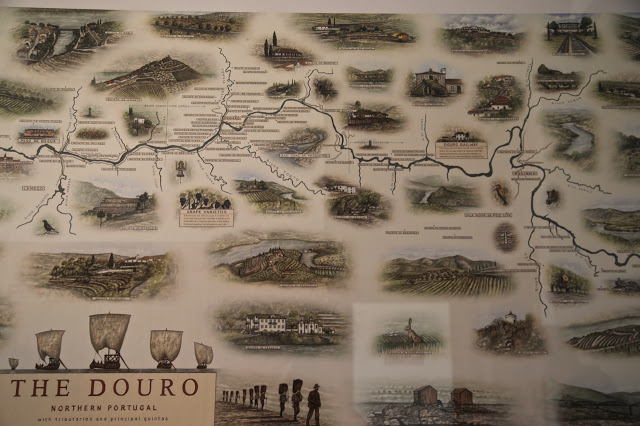

It was strange to be in Europe on the day that we voted to leave it. I’d landed in Porto, a picture postcard ancient Portuguese city on the banks of the Douro river. I travelled to the Quintas (chateaux) of five port and wine houses, collectively known as the Douro Boys, formed by five friends with wineries. Left to Right in the picture above the Douro Boys are: Christiano Van Zeller, the head of Quinta do Vale Dona Maria; Xito Olazabal of Quinta Do Vale Meao; Miguel Roquette of Quinta do Crasto; Dirk Van der Niepoort of Niepoort Quinta, lastly the owner of Quinta do vallado.

As the day wore on, I spent a small fortune googling the news on roaming. (By the way, don’t bother with ‘3’ network, reception is poor and data is expensive.) I was with a group of journalists from Austria, Germany, Poland, one American and one other British woman who, like me, voted ‘Leave’. She is from Chipping Norton, which lies in David Cameron’s constituency.

As a left winger Leaver, I’ve been in an uncomfortable position throughout the campaign. My attempts to meet other Brexit activists led to ending up in a pub with a load of Tories. Swallowing my distaste for their other politics, I soldiered on, but strangely was never asked to do anything – no campaigning, no leafleting, no meetings. The one meet-up next to Kilburn station was cancelled due to the sad death of MP Jo Cox. Maybe they felt that it was pointless campaigning in Camden and Brent, which ended up as two of the keenest Remain boroughs.

On the day of the referendum I travelled by road, train and boat to the Douro region. In the old days it took two weeks for a boat, pulled by oxen on the banks of the river, to travel to this formerly little-known area. The Douro wine trade really took off when the railway was built in 1898, then the journey took a mere five hours.

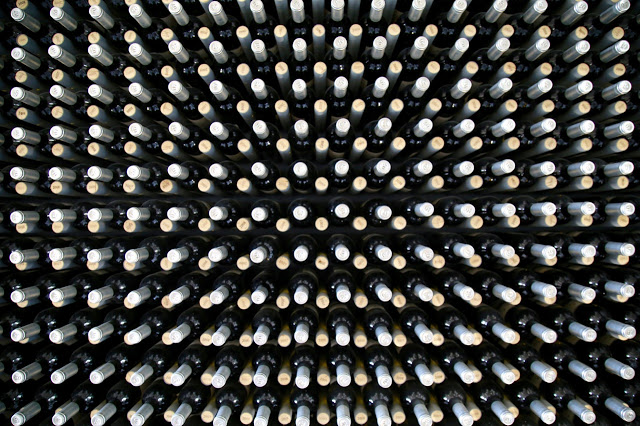

The Douro is often described as ‘nine months of rain and three months of hell’. At the end of June, it is around 35ºC, crushingly hot. Some of the time we spent in cool dank cellars that smelled of mould and spilled booze, a scent I’ve grown to love.

The Douro is one of the only domains in the world that still uses feet to crush the grapes. Each Quinta has glittering granite (lagares) tanks, where teams of 10 tread militaristically for 4 hours in sessions of 2 hours, back and forth, back and forth. The American journalist did it once and had to stop after 10 minutes. ‘It was exhausting,’ she confessed.

The advantage of using feet rather than machines is that the pips never get crushed, avoiding bitter tannins. The skins will be mildly broken and the body heat will trigger fermentation. You can’t get that kind of light touch with machines, although some companies claim that this is possible. The human touch must make a difference, perhaps even homoeopathically. Prior to the treading, the feet and legs are cleansed with a sulphur bath.

‘What about the hair on men’s legs?’ I asked Christiano Van Zeller, the head of Quinta do Vale Dona Maria.

He jokes, ‘it’s not a problem – if you get one in your teeth when drinking, you can just spit it out’.

He explains how the work is hard and often painful:

‘Afterwards your legs are red and itchy, caused by the yeast deposits from the grapes. Traditionally you scrub your legs with brandy, which kills the yeast.’

At the same time the Douro Boys have invested hugely since the ’90s in the most up to date wine-making technology, creating an effective synthesis of old and new methods.

The Douro is best known for Port, a fortified wine originally designed to suit the sweet English palate, particularly during the 1860s and 1870s. But over the last 30 years, since the Portuguese accession to the EU, the Douro wine industry has been reinvigorated. Portuguese wine is determined to carve out its own identity rather than ape French wines. Portugal has around 70 different varietals of grapes to choose from. The most commonly used Portuguese grapes are names that will be unfamiliar to most wine shoppers: Touriga Nacional, Touriga Franca, Tinta Roriz, Tinto Cao, Tinta Barroca. But this is sure to change.

The Douro, hard and hot, contains little soil, dominated by a kind of slate known as ‘schist’ that gives the wines a certain minerality. This ‘schist’ is unusual: rather then having horizontal cracks, the fissures are vertical, meaning that vine roots can reach 10 or 15 metres deep, tapping into reserves of moisture even during the dry summer months, avoiding the need for irrigation.

The countryside looks stratified, carved out of the hillsides, green vines trooping efficiently over the flinty contours. Each parcel, set on a different facet of a complicated puzzle, has its own character of grape. When looking, you can tell which are the older vineyards; they are untidy and yellower, with a variety of grapes known as a ‘field blend’. Tractors cannot access these unregimented vineyards. These grapes are often used for Port wines. DNA testing shows that in the most aged vineyards, there are up to 200 varieties of native Portuguese grape, still more are being discovered. I was stunned to discover that in new vineyards, wine makers can now change types of grapes every year, a technique I think they called ‘bubble graft’, simply by grafting on a new grape to the existent vines. This method is heavily used in Chile.

The wines themselves are impressive, the reds are big, fruity and spicy. I also tried some oaky whites, which I liked very much. The whites are usually grown on the higher altitudes so that they don’t ripen too quickly. At the Niepoort Quinta, run by lion-maned Dirk Van der Niepoort, the whites are picked early, around mid-August. As a result the wines are described by his winemaker Carlos Raposo as ‘elegant’, which turns out to be wine lingo for ‘acidic’, the perfect antidote for the scorching heat of the Douro.

Many people choose a wine solely from the design of the label. Niepoort have responded to this with cleverly designed individual labels for different countries, often referring to a local children’s book. In the UK, they sell a wine called ‘Drink Me’, invoking the magic of Alice in Wonderland.

Each Quinta has its own tale: Quinta Do Vale Meao was created in 1894 by a widow Dona Antonia Ferreira. She took the considerable risk of buying up land in the Upper Douro years before it had a railway. It’s now run by her great great grandchildren, a brother, the wine maker ‘Xito’ Olazabal and his sister Luisa.

Quinta do Crasto is led by movie star good looking, blue-eyed, dark-lashed brothers Miguel and Tomas Roquette. I put a photo up on Instagram and my personal Facebook. All my friends went ‘phoar’. My parents immediately asked when I was going to marry him. I replied that when it came to him Brexit wise, I was a ‘In’. My dad crudely replied, ‘In and Out don’t you mean?’. When I mentioned in updates that this Douro Boy had said hello to me, my mum optimistically asked, ‘Isn’t that binding in Portugal?’.

The Douro boys have set up a Feira Do Douro in June with food and wine stands, with Fado singers (below) singing the heart rending songs of traditional Portugal. It’s well worth a visit. One of the things the Douro wine makers are trying to achieve with marketing their region is making the link between the food and the wine. Like in Alentejo, the basic ingredients are fantastic: raspberries, tomatoes, cheeses, cornbread, fried potato skins, fruit soups, a great deal of meat based cuisine and hundreds of bacalao recipes for salted cod. Pastries are often based on egg custards, developed by the religious orders: the whites would be used to clarify the wines and the yolks used for desserts. There was a demonstration of how to make amendoas de moncorvo, chalky white almonds covered in bumpy white sugar, hand-roasted on a copper pan over charcoals, by a woman wearing thimbles on all her fingers.

On the Friday morning, the shock result of the referendum came through. Britain had voted to leave the EU. From that point on, between tours of vineyards and tanks, tasting sessions and meals, I had my head bent down, googling the latest news, in which crazy things seemed to occur every hour. The other British lady and myself were feverishly whispering to each other about the events.

We’d both voted Leave, but we were rather stunned to have won. I had a funny ache in my heart, a lump, rather like when you’ve dumped a boyfriend. You know it’s for the best, the relationship isn’t working, but still you feel guilty. Other people’s emotional reactions also dismayed me. On my Facebook feed, friends were acting like I was some kind of right-wing racist. I was tagged in posts about war starting again in Ireland, in posts about racist attacks, as if I were personally responsible. There were emotional tirades. Feelings ran high. I rang my daughter, a Labour activist, on Skype; her face was downcast and sullen. She resented me. I hung up. It did seem as if the Guardianista set, i.e. my friends and comrades, were talking about the ‘Leavers’ as if they were stupid and crass. People even questioned whether we should have had a referendum. Democracy itself was questioned, although I’m not sure if they realised that that was what they were doing. It felt like a civil war.

During the Port masterclass on the last day, I asked the Douro boys what effect Brexit would have on their trade. Sales of alcohol, like sweets, go up during a recession, but it tends to be cheaper brands. They replied:

‘As Britain has the most sophisticated wine public out of all non-producing countries, it will hit us hard. The UK is 15% of our market.’

Another chipped in:

‘I think that the English Port houses will suffer the most as they sell in pounds.’

But they agreed:

‘Britain is one of our oldest allies, eventually it will be fine. We’ve traded for hundreds of years.’

You do not say if this trip was paid for by a third party and yet you refer to being with a group of journalists. Please clarify.

I was taken by a wine PR to visit the douro. Happy?

I mean anyone with half a brain can figure that out, I'm not exactly hiding it.

As I don't get paid for my blog, or do sponsored posts, or host advertising, how do people think I get to do this stuff?

They haven't told me what to write.

Many of my trips are half press trip, half paid for by myself because I like to stay longer and research things in more depth.

Are you from one of the binder groups? It's kind of a snarky comment.

I am very pleased to hear you voted Brexit. The Left is perhaps not a lost cause.

I've been accused of being a tory. I actually think I'm more radical than many left wingers. Corbyn didn't believe in Remain, I wish he'd been true to his real feelings.

I voted remain. My brother voted leave and my other brother like me voted remain, but only just. I don't like the way no one sees the left wing arguments for leaving, it's all lumped into the racist camp. Anyway now I want to go to Porto!

Absolutely. Did you see Sienna wrote a blog post on this?

You'd love the Portuguese style and street art, it's similar to Spanish but with a Portuguese flavour.

My family and other Brexiteers? Yes it was brilliantly funny. She's a chip off the old block 😉

Thanks for sharing those amazing picture. It's really make me want to visit it.

OMG! How brilliant the photos are! This make me want to go there immediately!

Great post. I like a wine. Wine is so good. Great picture. I can imagine I go there drink wine, eat ribs, look the scene. So good.

Beautiful photos! I've still not been to Portugal but Port particularly has always been on my list.

Hi there any idea where i can purchase a copy of the Douro map?

No sorry, it was just on one of the winemakers walls. Cool eh?