Day One

Awake at 5am after 1.5 hours sleep. I hosted a supper club the night before and was cleaning up until 3.30am. I run for the coach from Finchley Rd to Stansted, coffee at ‘Spoons’, then take Ryanair to Copenhagen. At one point I think I’m not going to be able to squeeze my carry-on luggage into the metal suitcase measuring rack. A Ryanair woman looms over me. I remove my Wellingtons from my case, then the bag fits. I carry my rubber boots onto the plane in my hand.

I sleep through the flight, mouth open, snoring. Arrival at Copenhagen airport. My instructions say take a train to the meeting point in Sweden, in the Skåne area, where I will be picked up at 3pm by the organisers. I punch in ‘Hoor’ on the ticket machine. No such place exists. I ask for help and the young man with fluent English says you need to put the ö (those strike throughs and umlauts aren’t just alphabetic garnishes), it’s ‘Höör’.

In the wood panelled waiting room at Höör station, two smudge-eyed teenage girls are conspiratorial. I find a plug and charge up my iPhone. We will be staying in a forest with no electricity. I need every percentage point on my battery as I won’t be able to recharge for two days.

At 3.15pm I phone Charlotta: ‘I’m here’.

‘We’ll be there in five minutes, the others had problems catching the train.’

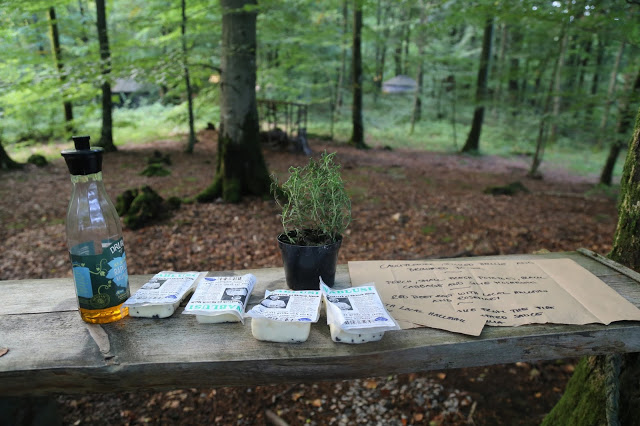

Lotta Ranert is a tall carrot-haired woman who has created this trip ‘Pure Food Camp’. She’s with Mia Klitte, a small blonde who runs a supper club venture called ‘A Slice of Swedish Hospitality’. We drive to Nyrups Naturhotell. At the entrance there is a dairy, Nyrups Osteria, run by Cecilia. She has laid out samples of her cheeses on a small cloth-covered table outside. As we walk through the forest to the camp, I slip. I’m wearing clogs. I’m told to change into my wellies.

The accommodation is yurts, with two red wooden beds in the middle under a central skylight under a green canopy of leaves. I’m given a separate yurt because I snore.

Camilla Jonsson is the owner of the Naturhotell. Her hair has become curly due to the menopause. We commiserate with each other. She shows us the compost toilets, separate ones for number 1s and number 2s.

‘But for number 1s, we pee in the forest.’

I like peeing outside. I don’t poo the entire time I’m there.

Camilla teaches us how to light the oil lamps and the paraffin heater. I think I’ll remember how to do it but not sure. I use the other bed to lay out my suitcase then walk to the motherlode yurt, which has a wood-fired stove, a dining table, kitchen equipment and supplies.

The other women

Gabriella Ranelli, 40s, of Tenedor Tours. She’s American but has lived in the Basque Country in Spain for 30 years. She’s a food writer, runs tours of the Basque region and is helping chef Elena Arzak to write a book. She often wears a black beret.

Regula Ysewijn, 34, from Flanders, is better known as Miss Foodwise, a food writer, photographer and currently judge on Belgian Bake Off. She is married to talented artist Bruno Vergauwen.

Helen Mol, 30, is from Berlin but ‘born in a Chinese restaurant’. She’s a wine expert and sommelier.

Emily Brown, 27, from England, can’t cook at all, she says. She organises tours with Martin Randall Travel that cater mostly for elderly people. She is learning Swedish and is planning to move to Sweden in a couple of years. Her biggest fear is one of her clients dying on a tour.

Keri Moss, 46 (but looks about 30), was a joint winner of Professional Masterchef UK in 2012. ‘I did it to prove that women chefs are just as good as men. People at my catering job laughed when I applied.’ She’s very close to her cats. She’s British from a Trinidadian heritage.

Sarah Krobath, 30, is from Vienna in Austria. She’s a food writer, author and journalist.

The head chef is Titti Qvarnström, 39, is the first female Swedish chef to gain a Michelin Star. Now between restaurants, she is heading up this project with Lotta. From Malmo, she tries to encourage a food community in the region. Titti is tall, slim with burning blue/green eyes depending on the light. Apparently Titti is a normal name in Sweden.

Titti’s husband Andre Qvarnström is here. He’s German and a chef, they met while working in Berlin. He’s taken Titti’s surname as his. Titti is filming an American TV show and so he helps with the camp cooking when she can’t be here. Andre and Titti don’t have metal wedding rings, they have triple tattooed bands on their marriage fingers, which is more practical in the kitchen.

We also meet Anna, 24, a young Swede, who is helping Lotta organise the camp. She’s a pescatarian too so I’m glad I’m not the only dietary difficult person at the camp.

After fika, we are given baskets of food to cook, either in teams or alone. I’m given halloumi and beetroot and told to do something with it. I hate beetroot. But you are always on beetroot duty when you don’t eat meat. It’s just a fact of life.

The beetroot is roasted until black in the fire. I slice up the Swedish halloumi with nigella seeds, made by local Palestinians, called Nablusi. It’s extremely salty (and I like salt); I later read that you are supposed to soak it in water.

There are several cooking fires, everybody is preparing a course. I grill the halloumi with rapeseed oil, crushed garlic and cider vinegar. We are only using Swedish products, so no olive oil. As darkness falls we gather around the candlelit table in the motherlode yurt. Each of us presents our meal, I’m apologetic about the saltiness and the charred messiness of my dish. People assure me it tastes good.

Regula has made perch en papillote and Keri has made a fire-grilled pudding, which was supposed to rise. Keri stands at the head of the table with an embarrassed smile, holding a dish containing a flat bubbly blackened mess. We divide it amongst us – it tastes fantastic, especially with custard.

As the night draws on and glasses empty, Regula mentions that she hasn’t cut her hair since she was 12 years old. She carefully undoes her red tresses from their complicated twirls and ringlets. The auburn hair falls to the back of her knees. This feels so intimate, as if she has stripped off naked.

Later she goes outside to pee, she returns almost immediately:

‘I’m scared.’

‘Do you want me to go with you?’ I offer.

She nods gratefully.

Outside, under the velvety canopy of the forest, we squat either side of a large oak tree and pee while chatting companionably. I return to my yurt, which I find due to the yellow glow from the centre window. The paraffin fire is lit, so is the lamp. Once I extinguish them, the yurt stinks unpleasantly of paraffin so I open the door wide and leave it open all night. I get up twice in the night to pee. In the pitch dark I can’t find my clogs so I go out to the forest in my bare feet. There was a rumour of Northern Lights tonight, so I look up, but there are too many trees to see the sky. In the morning I hear Regula and Keri, who are sharing a yurt, barely slept because they were afraid of zombies and bears.

Day Two

A Polish Swede called Pontus, who informs us he was named after a Greek god, is taking us on a foraging walk. He forms a circle and does physical exercises with us while we sing a silly song which lodges in your head, ‘Vi Kan dansa labado, lapado, lapadoo’, an ear worm.

We walk along the road to forage:

‘You must use your mouse eyes’ whispers Pontus ‘to see the small things’.

We collect stinging nettles. After pinching off a few stalks, I have a tingly finger. We use the seeds and the leaves. We collect hazelnuts, acorns, Spanish chervil, plantain leaves, chickweed and wood sorrel for salad. We deposit our finds back at the camp and set off again immediately through the forest.

It is a damp, autumnal season perfect for mushroom picking. I’ve never seen so many mushrooms, brown and fairy-tale red with white spots. I find some cep mushrooms, one bright yellow. The leaves are mustard; we see a coiled black and white diamond pattern viper, cloven deer tracks, horse shoe imprints, khaki toads. The walk is mostly uphill and I’m starting to feel tired.

At the top, Pontus does some focussing exercises; now we are encouraged to have ‘owl’ vision or peripheral vision, where patterns emerge. We stretch out our arms and listen to the silence. Pontus thanks everyone: trees, nature, people.

Cecilia Timner,the cheese lady, has set up a picnic. I immediately drink a beer. Now I’ve stopped walking, my body is cooling fast, I feel wet and cold. They’ve provided fish for me as a pescatarian, some sea bass carpaccio, but to be honest I rarely eat fish. It’s all a bit real. I eat cheese, fig chutney, crispbread and tomatoes.

The way back is much faster. I’m better at downhill, which might sound obvious but some people are terrible at going downhill and this is one of my specialities. We go to the motherlode yurt and sit on wooden low chairs with sheep skins and flop around the wooden stove. I can barely move. I’ve done 12k steps. That’s a fuck of a lot for a long morning. Eventually I stagger back to my yurt and write a piece on tomatoes, due tomorrow.

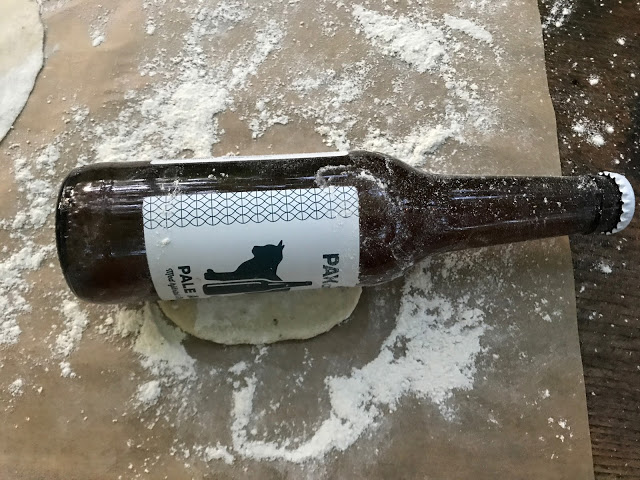

Then I come back out to the camp fire. I’m asked to make flat bread with nettle seeds and buttermilk.

‘Roll them out as thin as possible,’ says Titti.

Chef Titti is making butter in a tall wooden tube, using a wooden plunger, up and down. The butter is delicious and we keep the buttermilk for the breads. Emily cooks my flatbreads on the open fire; they bubble up and blacken in spots. I roll some more salt into them, scatter the seeds on top. They remain soft and pliable when cooked, like chapatti.

We try a Swedish speciality, ‘surstromming’, fermented fish. The orange and red tin looks innocent enough, then Lotta opens it and the juice squirts out all over her sweatshirt. The smell is overpowering, I can smell it from 50m away. It’s ammonia and corpse-like and the smell of rotting death. Regula cuts small fillets of it on a board. I take one and eat it. Ugh. It’s a little like pickled herring but with an odour of rotten egg. The flavour continues.

I walk away into the forest swearing, ‘Fuck!’ ‘Oh my god!’ and ‘This is just wrong’.

My brain is all messed up. We are supposed to eat this stuff in the flat bread. Fortunately there is some Kalix roe, one of Sweden’s protected foods (DOP). I spoon this, with sour cream, red onion and lemony wood sorrel, into my flat bread. It’s good. I don’t mind eating babies.

Pontus has been leeching shelled acorns since Saturday, changing the water every few hours. The soaked acorns now look like brown plastic or small fake Easter eggs. Titti puts them through a food grinder. I taste a bit. They don’t taste bitter but are very dry and tasteless. Acorns have carbohydrates and some protein. All of our food is local or foraged. Pontus intones:

‘Wild food is not put there by man. Acorns mean no fields of wheat.’

Night falls. For the main course, back in the cosy mother hut, we eat acorn burgers, buttery mashed swedes with potatoes, wild leaves and for the meat eaters, coiled sausages. Andre tells us to inspect our bodies for ticks with the torchlight in our yurts. I have a few bites on the back of my legs. I have no one to look at my body for ticks. I worry about Lyme disease.

Some people leave but some of us talk into the night: about the royals, about Lady Di, about illnesses, children, ambition and creativity. We drink Belgian sour beer and Austrian liqueur. Eventually I go to bed and sleep 8 solid hours without waking. This is good. It rains outside.

Day Three

I awake at 7.30am and, as we are leaving this place, leave my orange suitcase outside my yurt, ready to be collected. Regula is making Belgian pancakes on a cast iron pan on the fire. We are eating breakfast outside, the table laid with a blue cloth. The table looks like something from a Swedish lifestyle cookery book: pretty tea cups, local yoghurt with fruit compote, slices of cheese, fish, meat. A bowl of fresh butter. Coffee made the old fashioned way, the grains left in the kettle which settle at the bottom of your cup.

We walk through the forest back to the dairy.

The coffee and the walk have made my bowels move. I dash to the modern toilet in the dairy. We take a minibus to Elisefarm, a golf hotel with a spa. On the ride Lotta explains that Skåne is Sweden’s larder, where most of the food is grown. The owner of Elisefarm, smiling Ingrid, was a high-powered lawyer from Stockholm who fell in love with a local farmer from Skåne. They set up this business together.

‘What is this whole thing about golf?’ I ask.

Ingrid laughs.

‘I get the feeling that it’s about nice walks and drinking.’

She doesn’t disagree. I go up the wooden stairs and see my beautiful room, with two boat-like beds. I have a hot shower. The first time I’ve washed since Saturday.

We drive to a berry farm, café and farm shop, Brånneriets Gård, where we eat an excellent vegetarian lunch: leek and potato soup which the Swedes call Potatoleek soup – potatoes get top billing in Sweden. I pick raspberries, blackberries and seabuckthorn berries, the latter are like golden jelly beans. The owner Margitha Nillson teaches us to make seabuckthorn jam, pickled cucumbers and schnapps.

We are given a selection of ingredients from which to make our schnapps for our meal tonight: Spanish Coriander, Artemesia, Yarrow flowers, Chokeberries, Rowan berries, frozen Elderflowers (browned but still fragrant). I choose chokeberries, sweeter than the others and white yarrow flowers. Later we will fill our bottles with vodka.

On our way back to Elisefarm, we stop at a castle and look around the rooms. One room, small and narrow is totally filled with books and, next to the window, one perfect armchair. I want this room in my life.

Back in my bedroom I think I’ll write up my notes. I lay on my bed for a few minutes then wake up two hours later. Fuck. I wanted to swim.

I stumble outside to the heated outdoor swimming pool, the steam curling off into the cold. Twenty lengths then over to the spa for the Jacuzzi. There is also an outside jacuzzi containing rather drunk Swedes; mini wine bottles and beer are scattered carelessly around.

Tonight is meatball night. But chef Titti makes a vegetarian option for me, Swedish falafel or ‘Pealafel’. Målmo is famed for the falafel; it’s an immigrant food that they’ve taken to their hearts. Peas are very Swedish, so Titti has made a dried pea version of falafel, which is bright green and very good.

Titti Qvarnström’s face is all eyes, large pools, peeking out from a headscarf tied pirate-style, or a dark green hunting hat. She is as good looking, tall and lithe, as a model. But she’s got no attitude, no swagger or arrogance. No awareness of her beauty either. A rare woman.

Tonight we try Swedish wine, which is not bad at all. In fact I’ve often wondered, why the obsession with grapes when it comes to alcohol? Wine can be made from berries too. We walk in the dark, looking up at the stars, to the lake, where we will set the cages to catch crayfish. August and September is crayfish party season.

I hammer a stake into the grass and clutching a rope, chuck the cage into the lake. I manage not to let go of the rope and tie the other end to the stake. In the morning we will check the cages. The air smells of wood smoke. It’s not cold. For pudding we have berries and French toast. I sleep next to an open window and watch the full moon filter through the swaying trees, casting a silvery light.

Day Four

I wake up just before 7 with a dry mouth. First we collect our crayfish cages: I have quite a few. I now know the difference between male and female crayfish: the females are darker, browner. The males have two penises.

This morning we are going duck hunting. With tall hunters, clad in camouflage country clothes, one wearing corduroy knickerbockers, we stride along the blowy golf course, toward trees surrounding a lake. Golf grass is different: you can tell it is high quality and costly: tightly seeded bright, almost fluorescent green grass, I peer at the men and imagine them as Vikings, their descendants. One man has the complexion and wild eyes of a person who lives outdoors, and is swearing an orange high viz jacket. He has a dog, some kind of Labrador.

‘He’s very popular on hunts because he has a clever dog’ says one of the hunters.

He bustles around in the bushes and rustles up the ducks. He wears a bright jacket so that he doesn’t get shot. But ducks have good colour vision, so the hunters try to blend in. We are told to keep quiet.

Titti is wearing her hunting gear and carrying her father’s gun. She spent her childhood outdoors with her father.

‘I got my hunting license when my father died. Before I hunted on his license.’ she says.

The dogs are well trained, staying still during the shooting and running to collect the duck bodies in their mouths when directed. We remain silent, and every so often there is a call from the trees, some kind of human duck sound. The hunters tense, the ducks fly through the air and then shooting. At the end there are a dozen ducks laid on the grass, their peacock coloured necks stretched out. Those that aren’t properly dead have their necks snapped.

I don’t feel anything. I don’t eat meat but I don’t feel bad. I feel interested.

The only shooting I can try is with ‘clay pigeons’. I’m handed a gun, a beautiful gun with polished wood and engraved curlicues on the pewter metal. This is a ladies’ gun, with two barrels side by side, meaning you can shoot one bullet after another. Inside brightly coloured plastic cartridges, there are dozens of little pellets which used to be made of lead and are now made from steel. I’ve never seen a gun before which wasn’t behind a glass case in a museum. I’ve certainly never touched one or held one.

I am given bright pink headphones. Another man sitting at a machine a couple of metres away, catapults a clay object into the air. I watch the hunters hit the clay with ease. The noise is so loud, like dynamite. You can’t stop yourself from flinching.

I go to the line and stand with my legs apart, one in front of the other. Keep the gun tight to your cheek and your shoulder/ just above the armpit, I’m instructed. Look along the barrel, that’s how you direct your shot accurately. Take off the safety. When you are ready say ‘pull’.

‘Pull’

The weight, the length, the blast, the kickback. My whole body rings. It’s shocking.

‘Again?’

‘Ok.’

I step up.

Bang! I miss again.

‘Not far off’ says a hunter, smiling encouragingly.

I try a third shot.

Then I have to stop, to rest a while. It’s so physical. It’s both tiring and exhilarating. I feel exhausted and alive.

After a long pause, I shoot more. You can’t do many though, it’s too overwhelming, stupefying.

We have lunch with the hunters who are all local farmers. One, opposite me, looks very Viking, with pale blue eyes and white thick hair, strong teeth and a big grin.

It starts to rain and I’m offered a golf cart to drive back to my room. This is fun, like a toy car.

That night it’s the crayfish party which often takes place outside as it is a messy business. Elisefarm has a summer house with a fireplace in the corner, it’s perfect. The long table is decorated in red and white: small pointed cardboard hats, large bibs draped over the back of each chair, crayfish candle holders, crayfish confetti, crayfish streamers and crepe paper cutouts. On each plate, a little pair of pliers and a knife.

A large bowl of fire engine red crayfish is delivered. We are shown how to eat crayfish: you crack the claws, break off the body, extract the meat and suck the dill stock from the head. I don’t eat any. I stick to the smörgåsbord of cheese, crispbread, herring, salad, Västerbotten pie.

Every so often we sing songs, one to the tune of Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star. Then a swig of schnapps and:

‘Skål’! Cheers.

My chokeberry schnapps has turned dark purple. Our faces are bright and cheerful in the flickering candlelight.

That night, in my sleigh bed beside the open window, I have a restless sleep. My body cannot relax, I feel so tired but invigorated. The wind and the rain batter the window, like lead shot.

Day Five:

When showering I notice a large purple bruise on my arm from the kickback on the gun. This makes me feel pretty tough. I want to go on more survival type adventures.

Pack, meet at the hunting lodge for breakfast.

We see Pontus Dowchan, the singing forager, has joined Instagram and is commenting on all our photos. This makes us giggle. We joke that he will give up foraging to become a social media addict.

We meet back at the spa to give feedback on the trip.

‘It’s the best food trip I’ve ever been on’ I say.

Pure Food Camp will be operating commercially from 2019.

This article, how to type umlauts on a Mac, has been very useful in writing this piece.

I love the way you write. It makes me envy you on your trip to lovely Skåne. I felt that I could hear your laughter and sense the tastes and smells. gorgeous

Thank you Rhona, there was a lot of laughter!

Nice

I always enjoy your writing but this is one of your most vital and beautifully crafted pieces. Absorbing, informative, candid, immersive and poetic. Should win an award.

Thanks Sally, your comment has put a smile on my face. Makes the work worthwhile to get this kind of feedback. x

Beautiful writing, felt like I was right there with you. Such a personal and intimate style. ?

Thanks so much Kavey. Must chat to you about Japan as I'm planning my trip there. x

What a wonderful five days you had! Foraging for food, the camaraderie between you all and the sheer variety of activities….all described with such brio. Loved this piece….

Thank you Bridget. I hope to get the chance to do more of this sort of thing. x

Everyone else has said it but *wavey agreement hands* on the compliments. The trip sounds so cool, I'm gonna keep it in mind if I can afford it ever 😀

x

You would love it! And thanks for the compliment, frankly you can never get enough. The positive feedback inspires me!

Loved reading your account, though only have done so thoroughly today as I did not want to be influenced for mine! Great piece Kerstin, and yes so different from mine yet not so different! Unforgettable trip!!