My earliest memory is of Winston Churchill’s state funeral on a little black-and-white TV. It seemed to go on for days. I was mesmerised and asked relentless questions about death. I could not believe that we would all die. Me, my parents, everyone.

My earliest memory is of Winston Churchill’s state funeral on a little black-and-white TV. It seemed to go on for days. I was mesmerised and asked relentless questions about death. I could not believe that we would all die. Me, my parents, everyone.

I was there when Princess Diana died, in Paris, arriving at the tunnel, black screech marks still marking the road, just after her smashed car had been lifted out. Back in London, outside of the Kensington High Street tube a mile away, you could smell the fields of laid flowers of Kensington Palace. I watched the funeral on the giant screen in Regent’s Park, heard the rippling applause for her brother’s speech, cycled to see her hearse, windscreen piled with thrown flowers, crushed carnations under the wheels, make its way north from Baker Street.

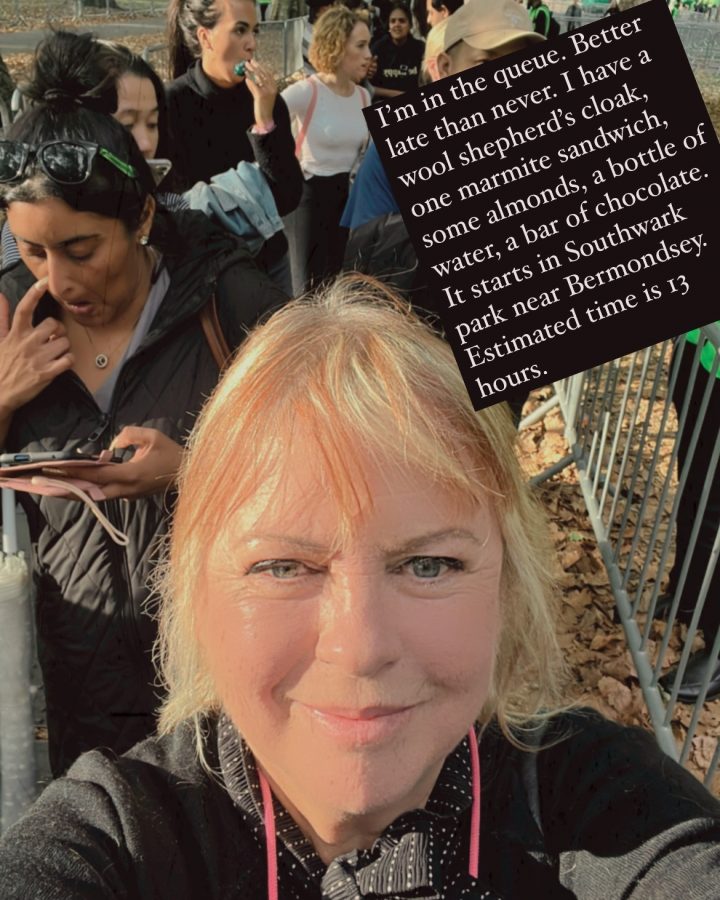

So I had to do the queue.

Eight and a half hours it took me, starting at 5pm on a Sunday, finally reaching the coffin to pay my respects at 1.30am on Monday. Five hours later, the Queen’s lead-lined coffin would be heaved out, the weight of half an Aga, by six young men in red uniform, white gloves clasping each other’s shoulders, to be placed upon the gun carriage pulled by hundreds of naval ratings in blue and white.

I started the queue from Bermondsey station. virtually running to Southwark Park. I was worried I wouldn’t be able to see her. The route was lined by black notices showing the way to the Queen’s lying in state line.

I saw the press gathered at the end of the queue then followed the metal barriers, all the way to Tower Bridge where the queue started in earnest. People had set up stalls outside their houses, selling hot drinks and snacks. I needn’t have worried about taking food and drink. I was given water, hot drinks, piping hot crunchy sweet churros and a basket of chips, by queue mates. Volunteers handed out ‘Heroes’ chocolates.

There were various forms of entertainment along the way: one hi-viz jacket usher doing a comedy skit; a random guy on a bicycle doing a speech about animal rights with a loudspeaker; musicians doing indie rock or better; the plaintive whine of a lone female bagpiper walking up and down.

I saw the sights of London: the river at high tide; the bridges; the Wheel; St Paul’s in the distance; a glorious Dubonnet daubed sunset backlighting the queue.

My queue mates consisted mostly of women from Essex: a mum and daughter team, the mum of which I gave a spare pair of socks as she was limping barefoot due to a blister. I didn’t know that Uggs were worn without socks. The daughter and her friend got selfies with every handsome soldier en route. Another mum and offspring team; this time a transman with a full beard and a pretty soft face. They were funny and nice handing out ‘Babybel’ cheeses, referred to as ‘power cheeses’ when our energies were running low.

There was a posh blonde guy in his 20s queuing on his own. Further up I saw an older man, holding a black jacket with a row of medals pinned to the pocket, who had that short stocky look of the ex-soldier. Some were in wheelchairs (I envied them briefly – at least they were sitting down) and others were elderly and clearly in pain. But still they stood and waited, not cheating the line.

It was a diverse crowd: every race, colour and creed, every class, every age, every sexuality or gender. I saw a family of Hasidic Jews, I saw Hindus and Muslims, Scottish, Irish, Welsh, American. I was handed Christian tracts en route.

We stood. Sometimes the queue hurried ahead and we’d have to catch up with our queue mates. You formed a bond.

- Abandoned seats

- I passed a merry-go-round

When we crossed the bridge past Westminster, we felt nearly there. Queue calculations were being mathematically assessed. A ten minute section of ‘walking’ on Google Maps was the equivalent of half an hour’s real time – ooh, we’d be there in an hour and a half, we told ourselves. Another guy said if we divide the miles by 30 centimetres, the depth of an average human, then… ah forget it, we couldn’t do the maths.

The atmosphere was not sombre despite the cause. There was laughter and selfies. I was in black, most people weren’t. I wore my wool shepherd’s cloak bought from a market in France. It kept me warm and dry (wool repels moisture), but we were lucky with the weather: it was pleasant and didn’t rain, barely spitting for a few minutes.

Finally across the river, the zigzags start. Within sight of Big Ben, the queue slowed down, up and down, up and down, it was no longer about distance but time. My knees started to ache. I tried not to drink too much water as I wanted to avoid the portaloos. But anyone in catering knows dehydration equals sore feet.

We started to hear rumours about security. We were only allowed to take in a certain sized bag, Ryanair style. All food and drink must be thrown away at the end; nothing could be taken in. I saw a guy with a flask. ‘Will you throw it away?’ I asked. I had a new metal water bottle. ‘No, you can just empty out the liquid.’ I threw away my almonds, picking them out as they had spilled into the bottom of my bag. I gave my untouched chocolate bar to a food bank volunteer.

No makeup was allowed. I had my £40 Mac lipstick in my bag. I considered hiding it in my bra. Then reluctantly chucked it into a bin. Armed police went through every single bag. Then we walked through airport security, a scanning machine. ‘No more zigzags,’ said one man encouragingly as we filed though to Westminster Hall.

Smart men in tailored suits stood at the side of the queue and stared: pleasantly but with sharp assessment. They looked like intelligence. Somebody had tried to rip the flag off the coffin two days prior: a man who, significantly, talked to no one in the queue. Imagine spending that many hours with someone who didn’t speak. You’d know they were up to no good.

The mood hushed as we entered the hall. A changing of the guard was taking place, but I couldn’t see. Finally on the steps, looking up at the wood vaulted ceiling, an enormous medieval structure. The waxy smell of candles and musty odour of great age. Then down the great hall, the tiny coffin on a stand, wrapped in a gaudy gold and purple flag. Red-clad soldiers around the coffin then another layer of guards: Beefeaters, older, standing, leaning on crooks. Solemn as the grave.

I walked down the carpet, stopped in the middle and bowed my head. I would have liked to have lingered a moment more, but my legs were hurting too much. I walked to the end where another queuer was stood oddly with a book in his hands, in a horizontal position. That’s a bit weird, I thought. As I passed him I heard a voice shout: ‘No photographs’. He must have had an iPhone hidden in the book. Up to no good, you can always tell.

I’d done it.

The worst part was getting home. The exit tried to funnel us all south over the river. But I live in North London? ‘It’s one way now,’ said a volunteer. I groaned. My strength was failing me after a 12-hour journey the day before from Italy. It was 2am and I was suddenly so tired. I managed to track back into Parliament Square where people were huddled in tents and on pop-up chairs, four-deep away from the barriers.

A policeman let me cross as I headed for Victoria Station where I knew there was a night bus home. But as I walked the roads were closing around me for tomorrow’s funeral march. I waited for the night bus. It didn’t arrive. I found a bus driver: ‘We can’t get here, all the roads are closed, I was sent on an hour and a half diversion.’

A few minutes later I saw a black taxi with a lit yellow light, I hailed it and spent £40 on the journey home. I’d done 32,000 steps.

On the Monday I watched the procession on the TV. The mournful affecting pipes and the snare drums, the swaying shoulders of the navy lads, the tiny steps, 75 to the minute. It’s the music that gets to me. Princess Anne wearing a masculine uniform, trousers, not like the wives in the cars, showing she is as every bit as equal as her brothers, sons and nephews. I would have liked her to be Queen. I’m not looking forward to three generations of kings; it seems wrong now.

On top of the coffin were clashing flowers from King Charles to his mother which seemed a bit nan-like to me although I liked the inclusion of a sprig of myrtle grown from her wedding bouquet. The speeches in church were dull and flat from pudgy pale-faced churchmen. Baroness Scotland, despite her dodgy reputation on expenses, gave a good reading, full of austere expression, her red lipstick beneath a black hat.

In the Apple store yesterday, someone noticed my queue wristband that I am still wearing. Get it laminated, he suggested.

- The wristband

- Teas and coffees

- The waiting crowds in Parliament Square

- Flowers tucked into trees

Brilliant.

Lovely read, feel like I was there now. Thank you