The harvest and the pickers

The harvesting of sweet grapes in Bordeaux fascinated me. This area, south of the city, has damp misty nights, foggy mornings and sunny windy afternoons. Perfect for the characteristic development of botrytis (noble rot).

I arrived at the beginning of the vendange in September. This year has been good – plenty of sun and just the right amount of rain. The winemakers were happy, their faces relaxed, their welcome expansive. It’s going to be a good vintage.

Not anybody can harvest sweet grapes. You need to be trained.

‘There are 50 traditional gestures for picking the grapes,’ the guide at Chateau Yquem informed me, making it sound like an ancient form of mime. ‘The pickers each have their own plot, which they look after all year, getting to know each vine. They protect every vine by covering the roots in winter, green pruning in spring and thin the leaves on the eastern facing plots so that each berry can get the maximum sunlight.’

To take part in the sweet vendange, you need to live locally. The grapes are gradually harvested, berry by berry, in at least three stages over six weeks, so your work days will not necessarily be consecutive. Every week or so, the pickers go around to see which grapes have shrivelled, concentrating the sugars to make the celebrated sweet Bordeaux. They pick only the most rotten grapes.

‘Women listen to instruction, are more consistent and concentrate better,’ one grower told me.

The experienced and the newbies work opposite each other. After a demonstration, I tried myself. You have to pick the right bunch: not too many green grapes.

You cut the bunch in half to see if there is white mould in the middle. You are looking for green mould, not white and definitely not black. It’s a sticky, mucky job. Your hands are covered in black soot. At the end of the day, your hands ache from using secateurs.

Each vine has approximately six bunches of grapes. By the time the bad mould and the unripe grapes are cut off, you have enough for just one glass of sweet Bordeaux. That is why it’s expensive.

Sweet Bordeaux has a low yield. The vines are planted closer to each other: 80cm between rows rather than the usual metre. The grapes are a blend of Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc and Muscatelle. The vines look like poodles, all spindly legs and leafy bubble cuts.

The growers, owners and winemakers

Chateau Yquem

Yquem is most famous for sweet white wine but it also makes a dry wine enigmatically named just ‘Y’. To buy this wine you must be invited – you can’t just go to your local off license. Their yields are low, only 10,000 bottles, costing 135 euros each. Standards are so high that in 2012, Yquem decided not to issue the vintage; the rarity all adds to the luxury goods mystique.

In the year 2000, they only issued 25k bottles of the sweet white. Prices reached half a million euros per bottle. In 2014, a bottle of Yquem cost 350 euros.

The Chateau Yquem tasting, held in a golden room with rich Chinese tourists whose children touted cameras worth thousands of pounds, managed to penetrate through my sugar-induced fatigue. (I have to admit that tasting up to 30 sweet wines in a day was difficult, and they all tasted similar in the end.) But Yquem Sauternes wine, while sweet, has a thin spine of steel running through it, rendering the honeyed sweetness bearable.

Chateau Sigalas Rabaud

We enjoyed a rare visit to the Chateau Sigalas Rabaud, where the elegant chatelaine and owner Laure de Lambert welcomed us into her house. (It should be remembered that most chateaux in Bordeaux until recently did not allow tastings or visits, unlike other areas of France.) Renegade chef Olivier Straehli, who only became a professional chef in his late 30s, made one of the more interesting matching menus of the trip, combining Sauternes with courses containing espelette pepper and dark bitter chocolate.

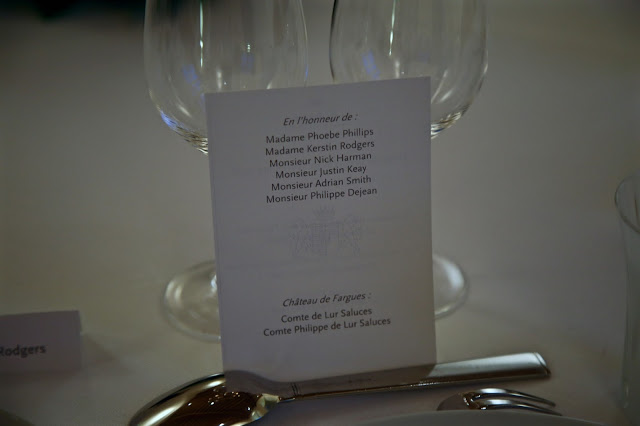

Chateau de Fargues

At a formal meal (see the dinner cards above), I ate with Count Alexandre de Lur Saluces and his son Phillipe, who, while looking like a city banker, was charming, humorous and fascinating to talk to. The dad, Monsieur le Comte, on the other hand, was a bit scary. When the chef asked ‘did you like dessert?’, Count Alexandre snapped back, ‘No’.

Chateau Yquem was owned by the Lur-Saluces family until 1996. Comte Alexandre, who was resident, only owned a small percentage and was forced by family squabbling to sell to LVMH, the luxury goods company. I asked Phillipe about the sale while lamenting that wine chateaux were being bought out by large companies.

‘Is it the right decision to sell your family’s land, your ‘patrimoine’, your ancestral birthright?’ I queried.

‘Unfortunately, with the French system of inheritance, we ended up with about 100 owners. Some of them needed money. It’s all very well having a sense of duty to your land but if you haven’t got enough money to buy your own flat to live in…’

I saw his point.

Still, all was not lost for the Lur Saluces family for this dinner took place in their other castle, Chateau de Fargues. Fortunately they had a spare. The Lur-Salaces are one of the oldest families in France. Phillipe’s (great great great great) grandma Françoise Josephine de Lur Saluces was a real character. Sole heiress to Chateau Yquem, she was orphaned at 16, married to the heir to Chateau de Fargues at 17, pregnant at 18 and widowed at 20. Jailed during the French revolution, this single mother managed to keep her head and run the estates while in prison. At this time, Phillipe explained, noblewomen did not run businesses so she was regarded as quite outrageous, a feminist of her time. The lady of Yquem then introduced new techniques to her wineries, such as cellars, the system of late harvests, picking in stages. She died at the age of 83.

After dinner, having had a few too many glasses of sweet Bordeaux no doubt, I asked Phillipe if he was an aristocrat.

‘I’ve heard,’ I said, ‘that if you have a ‘de’ in your name, you are an aristo.’

‘Yes.’ He nodded.’Have you got a ‘de’ in your name?”Yes, I have.’ He smiled.’So you are an aristocrat?”Yes.”What about your wife?”She’s an aristocrat too. She also had a ‘de’.”Wow. Is that like a coincidence or what? Or did you only hang out with girls who had ‘de’s?’

Phillipe seemed not at all bothered by this line of questioning. He proffered, completely unfazed:

‘My mother wasn’t sure, she was worried that they were a new family…’

‘Like, with a fake ‘de’?’ I butted in.

‘Yes, but then she looked at a book with my grandmother and they found that my fiancée came from a very old aristocratic family so they were very pleased.’

I boggled at how different life must be if you are properly posh.

‘In China you can’t match food and wine because of the way that they eat. They’ll have around 12 dishes for everyone to share, some red meat, some white meat, some fish, some vegetables… and everyone will share. So they use wine as a toasting drink, before the meal. They knock it back in small tumblers.’

Chateau Laville

‘Sweet wine is very complex,’ says botrytis expert and Bordeaux professor of oenology Jean Christophe Barbe at Chateau Laville, his family estate. I called him the Professor of Rot.

‘Most wines have 1,000 aromas but sweet wines, because of the noble rot, have closer to 3,000. The grapes we use for ‘pourriture noble’ are thin skinned – it attacks the skin first. For noble rot we need dry conditions on the berries. If it is too wet, grey mould appears. However in Bordeaux we are not allowed to irrigate unless you have a special permit from the authorities. Irrigation is very expensive, 15k euros per hectare.’

We sat at a white clothed table in a dark room, tasting wines that danced with banana, grapefruit and orange zest flavours while Monsieur Barbe’s elderly aunt chatted in a back room.

Bastor Lamontagne

She is relaxed about the idea of using it in cocktails, as in the ‘Sojito’, a Sauternes version of the Mojito, adding Perrier and mint. I didn’t get to try one unfortunately. Margaux is less strict than other winemakers, who regard this as abhorrent and demeaning to their wine. Bastor Lamontagne, in contrast, has a different attitude, producing a lighter blend called Caprice, as well as the traditional Sauternes.

Chateau du Cros

Winemaker Catherine d’Halluin Boyer invited us to eat in her kitchen at Chateau du Cros at Loupiac. This was the ‘new’ chateau. The old one, a ruin that is gradually being restored, dates from the time of Richard the Lionheart in the 12th century. Tourists can do a tasting and the walk to the castle, which in June features a medieval fair. We had a vegan lunch prepared by Bordelais chef Aurelien Crosato, who is known for his experimental cooking. His tiny Asian-American wife Serena filmed the whole meal. Chef Crosato matched sweet Bordeaux with fermented foods and pickles, which I thought worked very well. As this wine is usually drunk with foie gras and meat, it was a welcome change for me. My one problem in the Bordeaux area was the lack of vegetables with a meal, the absence of vegetarian courses. In some ways Bordelais cuisine is dated, still reliant on huge hunks of protein occupying central territory on the plate rather than employing the fantastic vegetables available in the market.

Chateau La Grave, Sainte-Croix-du-Mont

‘The French can’t cook curry,’ I blurted rudely.

I don’t have much of a filter anyway but I was becoming tired and emotional.

Chateau Rayne Vigneaux

‘Tu dois etre en forme.’ (You must be fit.)

It’s not dessert wine

Sweet Bordeaux has become less popular, described by Victoria Moore as ‘off trend’. While Bordeaux supplies 45% of French wine, only 8% is white, of which 3% is sweet. There are attempts to make sweet wine more accessible but in an age where sugar is demonised, this isn’t easy. Sweet Bordeaux contains no added sugar, it’s all natural, but each litre of the noble rot grape must contains between 300 and 600g of natural sugars.

The real issue is that we call sweet Bordeaux ‘dessert wine’ when it is nothing of the sort. It is drunk in France as an aperitif, before the meal. The biggest lesson I learnt was that this wine does not go with dessert, in fact it kills it. The dessert wine designation stems from a time when people would have a glass of sweet wine in place of dessert. The trend in modern wines is towards less sweetness, especially in the UK, which has a sophisticated wine buying public. For instance, in the UK we never drink sweet or demi-sec champagne, whereas in France they still do. Brut Champagne was developed for the British market.

Sweet Bordeaux does match absolutely perfectly with cheese, particularly blue cheese.

If matching with dessert, choose dark bitter chocolate or perhaps a little candied chilli or walnuts or citrus. Those massive almost overwhelming sweet Bordeaux flavours need to be tempered and opposed.

Sweet Bordeaux is an investment because it can span a lifetime: you can keep a bottle for up to a 100 years. It is thrilling to see dusty antique bottles in cellars dating from the beginning of the 20th century. As Jean Christophe Barbe comments:

Wine tasting is like communing with the dead.

Sweet Bordeaux changes over time in hue; from a pale wheat to rich gold and finally a deep amber. The potential ageing means that high quality, long corks (54mm as opposed to the usual 45mm) are used, which can last a century or more. Yquem suggests serving the young sweet whites at a cool temperature of 9º and a little warmer, 12º, for older vintages.

Leave a Reply