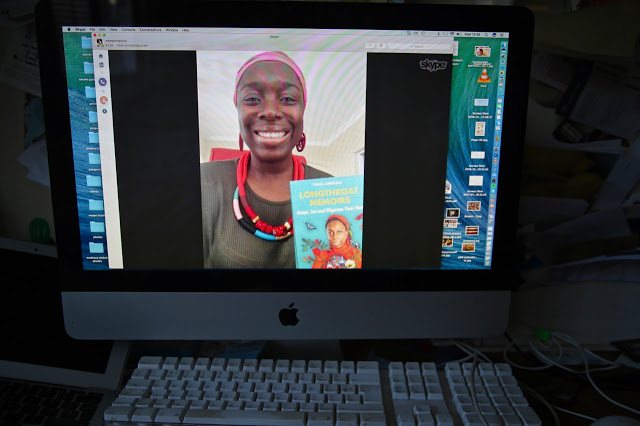

Yemisi Aribisala is the author of ‘Longthroat Memoirs, soups, sex and Nigerian Taste Buds’, which is shortlisted as best food book with the Andre Simon Book Awards. It’s wonderful to read a book by an African food writer: we rarely hear about African food, or Nigerian food, and we certainly don’t hear much from black food writers, from any continent. The book is poetic, emotional, funny, and honest. One chapter in particular, The Snail Tree, took my breath away. Here was a writer combining feminism and food in a way that I hadn’t read before. Unfortunately she couldn’t attend the awards here in Britain, so I interviewed her over Skype from her home in South Africa.

Where are you right now?

In Somerset West.

Oh, you live in Britain?

No. I used to live in Britain years ago, but this is outside the Western Cape in South Africa.

You’ve got three kids to look after by yourself, so you haven’t got much time for writing.

Yes, I do it when I’m doing the washing up.

Don’t you find the flow of water helps the muse?

Yes. Housework is good for that too. When I lived in Nigeria, I lived in Lagos. But the book is based on Calabar, which has a border with Cameroon.

Do you miss Nigeria? Is it hard living in another country?

If you are busy enough… I find it very difficult to be bored. It’s all relative – what is hard?

Your book is beautifully written, magic with words. In some ways it slightly reminds me of The Famished Road by Ben Okri. He often talks about ghosts. In your book you talk about spirits, almost witchcraft. Is that part of Nigerian culture?

It’s very interesting, I would never have put the two books together. I found the Famished Road very difficult to read, very heavy. I hope Longthroat Memoirs is more accessible.

Yes, it is indeed.

We are probably more spiritual, we go to church or to mosque, and because of that we probably think a lot more about these things.

It’s almost like there is a very thin veil between this world and the spirits. Is the veil thinner in Nigeria?

(Laughs.) Maybe it’s an African thing as well. That’s an interesting observation. The witchcraft is supposed to be funny, I’m not taking this as seriously as maybe the average Nigerian would take it. There is a thing about women who cook, they are dangerous.

I fully admit to being a witch. I can control people with my food.

You know how it is, there’s something about cooking a meal for people. I find that people sit down and they come for a meal and they tell you everything. How do you explain that thing?

It is important to cook with heart. Here in the West, we never really talk like that.

I didn’t want to give off that spooky — it’s not a meal, it’s a seance. You have to be able to laugh about these things.

That chapter that I really loved was The Snail Tree, about food, feminism, sex, homosexuality, abortion. It kind of broke my heart; it’s a very emotional chapter. Most food writers aren’t writing about those things.

Even in Nigeria when you want to write a book, you already have that pressure. I wanted to write something really genuine. Everybody wanted me to write about competence. A lot of the time I’m incompetent in carrying out this thing. There has to be this happy go lucky, sexy thing about it. I’m a mother of 3, I have a soft belly, I can’t, I can’t pretend.

Yes.

I couldn’t put the names, I can’t put my friend’s name. It was the experience of three women, I had to protect… including myself. There’s something about writing your own story that sounds a little bit self indulgent. If you can put it out on the table, it’s easier to look at, it’s easier for everyone to look at it. True story.

Very important subject.

The parallel with the appetites, it’s easier to talk about sex with food.

Especially as a menopausal women. I don’t have sex, I’d rather eat. It’s more reliable.

You can trust, it sounds a bit cynical, you can put your trust here into food.

Absolutely.

You can eat a nice meal and you are going to be happy and there is nothing else.

Yes, it’s not going to break your heart.

I’m just going to throw some disjointed questions at you.

The writing is episodic, each chapter is like a short story. I’m a blogger too. That’s kind of how we write. Blogging has brought back the short story.

It’s easier to read as well.

Why do Nigerians believe in God so much?

Hmm, it’s an interesting question. Why don’t you believe in God so much?

The UK is a post-Christian nation.

Yes, I did live in the UK for a bit. I remember that, what the churches were like. It’s not a huge affair like here. It’s hard to say why, I was brought up going to church but I barely go, I don’t go. It doesn’t stop me believing.

Over 50% of Nigerians are Muslim now, aren’t they?

We are religious. That could relate to the idea of spirituality being important. If you are engaging in spirituality every week, you go to the mid-week service, you go to church, you go for the prayer meeting. You go in and out of it. You are the first non-Nigerian interviewing me. No one has asked me that. It’s so much part of our life. It’s an outsider’s point of view.

Also in London, one of the ways that Nigerian culture is most visible here, to me, is that Nigerian churches have taken over the places where we used to have rock ‘n’ roll gigs.

I had no idea. Are you serious?

Yes, like the Rainbow room in Finsbury Park, where I saw David Bowie. They shut down, now it’s a Nigerian church. Where I live now in Kilburn, the Kilburn Gaumont was shut down, now a Nigerian church.

Everything you are saying is like a revelation. Rock ‘n’ roll is the common factor. We are very loud, aren’t we?

I’m loud too. I’m slightly allergic to religion as a lot of British people are. In a sense, I was brought up with rock as a kind of religion almost. We believe in David Bowie. That’s why we were all so devastated when he died. It was like a god had died.

There is a parallel there. We’ve had these pastors in Nigerian churches, who are dressed up in very expensive clothes. They live like superstars. It’s not far-fetched. A lot of people go because of the charisma of the man. There is a spiritual gravitation towards these places.

Do you think that is why, subconsciously, they are taking over the rock ‘n’ roll spaces? I’ve never actually been in one to see the church ceremony. I’ve seen women outside beautifully dressed on Sundays, the headdresses, the golden head wraps. I should go to one.

I’ve never actually been to a mosque. I don’t want to stand out.

There’s humour and cynicism in this book, which I love. For instance: ‘Africa is in.’ You talk about branding. You say: ‘I may even win a foreign prize, and I’ll pretend not to love it.’

I try my best not to be pompous. I don’t want people to think, ‘she’s better than us’. In real life, I’m actually glad I’m not coming to the awards as I have the worst social anxiety. I have strange facial expressions, I can’t control my face. (Laughs.)

I think quite a lot of writers don’t feel that comfortable in social situations.

It’s very hard.

The only reason I want to go because it will take place in the Goring Hotel, where Kate Middleton went before her wedding.

Very posh.

What do you think of Alexander McCall Smith?

I listen to the audio books when I wash the dishes. I bought the one that made into a TV series with that beautiful lady Jill Scott. I watched it over and over and over. He doesn’t write very nicely about Nigerians. He writes nasty stuff about us. I don’t know why that is.

I went to Botswana a couple of years ago, I went on a tour, to the house of Mma Ramotswe. McCall Smith spent many years there.

She’s not real!

But it was based on real places. I really enjoyed that, but one of the debates now is about cultural appropriation. Do you feel culturally appropriated?

No, I don’t feel culturally appropriated. Maybe it’s because it’s not Nigeria. Because it’s Botwana. I love Mma Ramotswe and her relationship with Mr J.L.B. Matekoni. I love that nothing dramatic happens. There’s just enough trauma. There’s enough trauma on Facebook. Sometimes it’s tough to find stuff that doesn’t traumatise me. Sometimes I just leave out the politics because I want to enjoy the contents. You know he loves Botswana. I think sometimes we over-drag this thing.

I’m sure I put my foot in it all the time. I went to a dinner party, there’s this man standing with this lady and I say, ‘oh is this your daughter’, and he said, ‘no it’s my girlfriend’. I wanted to enter into the ground. I want to be able to forgive.

One of the things I like about his work, and you mention it, is the ‘traditional shape’ that African women have. I’m a traditional shape. Shall I just stand up and show you my traditional shape?

(Laughs.) This is something I feel really strong about. I’m a mother of three. There was this guy who was chatting me up on Twitter. He obviously thought that because I was a foodie, that I was larger. He was saying, ‘I like women with big thighs’.

Why isn’t a big fat belly an erogenous zone?

(Laughs.) Yes. It’s very hard to enjoy your food. It’s so hard, it’s ridiculous.

I liked your cynicism about branding.

I spoke to a TV producer and said, ‘I’d like to do a food show, would you air it?’ He said, ‘no I want someone else because she’s very slim and fabulous. I know what you mean because you think but she can’t cook.’ He said: ‘It doesn’t matter. We are just going to let her stand over the pots and just look gorgeous.’ I already have body issues. Maybe that’s why I prefer to watch men cook. They don’t feel that pressure.

Is English your first language?

There are so many languages in Nigeria, we’ve had to compromise and speak English. It’s not my first language but it’s the language we go to school in.

What language do you count in?

English. I speak Yoruba very well, it’s just I wasn’t schooled in it.

In the book there’s so many African/Nigerian words, I almost wanted a glossary.

That’s political, there’s a discussion now that’s going on about this. When I was in Britain, people asked, ‘can I call you Angela?’

They are saying that because you have an African name?

In London, yes. Don’t you have an English name? It happened all the time. It’s better now though. Nigerians are so well travelled. We go to countries and we learn to speak their language, we learn how to say their names. It isn’t super human. It’s not rocket science.

I can show you how many words I’ve circled in the book, but by the third chapter I’m starting to understand it.

That’s the thing though, isn’t it?

As a British person, when I go to an Indian restaurant I’ll order practically in Hindi. I’ll say can I have a matar paneer, a brinjal bhaji. If I go with an American, they would be like ‘what the hell are you saying?’ We go through an osmotic absorption of another language through its food. That’s what happened to me reading your book. Eventually I understood the words. So for instance, dawadawa is like fermented…

It’s the locust bean, hard to describe.

I want to try that.

It has a very, very strong aroma. Thai fish sauce doesn’t hold a candle to it. It’s a lot stronger, like cheese. People make it in different ways. Sometimes you can smell a bit of chocolate, sometimes it’s more musty.

Is there much vegetarianism in Nigeria?

No. My publisher is vegan. I had this feeling it was hard for her to engage with the food in the book because we eat a lot of meat – not as much as Kenyans do, but we eat a lot. I know the Northerners have livestock. Same in Botswana, any country that has that livestock herding culture, they eat a lot of meat. You can see the divisions in our cuisine.

Is it to do with the terrain? I’ve never been to Nigeria. In Botswana it’s very dry most of the year. They have one wet season, the delta where there is a lot of greenery, and they can grow stuff. Most of the country it’s scrub. You have different terrains in Nigeria.

In Nigeria, if you go north, the heat is very dry. I come from the south west, Calabar, it’s very humid, rainforest. This is a problem for me here in South Africa: it’s really hot and dry. People say that it’s ridiculous, why is a black African woman complaining about the heat? It’s a different kind of heat.

Even in Cross River state, you can just drive, there is a mountainous bit, 1,500km up, and it’s like you are in Britain. There are different eco-systems. How do you explain the food? The food moves up and down a lot. We are eating from a lot of different places now. We are sitting in Cape Town and we are eating everything. We are eating beans from Kenya. Eating seasonally is gone now. Calabar was like a hub. We have trucks coming down from the north, beetroot and carrots. Palm oil coming from somewhere else. If you live in the town, you see all kinds of things. You find ridiculous things, like chorizo sausages and expensive teas. It’s very international in Lagos.

It’s called arm choreography. First a piece of the mound of pounded yam, gari or fufu, is pulled off and rolled into a ball. It is depressed with the thumb to form a spoon and then the spoon is used to scoop the soup. The soup is reluctant or asleep and an effective scoop involves invading the soup and pulling away with a brisk tug of the arm. This is no ordinary tug, it is skilfully done so that the soup breaks away neatly without drawing messy patterns all over the utensils and the table.

Let’s talk about slime.

Don’t call it that. (Laughs loudly.) I knew this was coming.

Africans, and sorry I’m talking about the whole continent here, you love a bit of slime. In the soup you have the okra, which is the only vegetable I hate because of the texture, it’s mucilaginous, you talk about the draw, how it’s gotta to be not too thick.

This is me. Some people cook it and it’s like this, stretching gesture, like lycra. I want to put cinnamon in ogbono soup. The people snubbing mucilage, look at cinnamon! Get the powder, put it in the bottom of a cup and pour a little water on it.

You think cinnamon does that too?

Yes, it’s incredible.

When I interviewed Fuchsia Dunlop, we talked about how the Chinese like texture. In the West we are very conservative about texture. Why do Africans like mucilage? Even some of your yams are gooey.

There are all kinds of theories. We eat a lot of starches and you need something to move it.

It’s a digestive thing?

To actually put it in your mouth and make it move. I don’t eat the starch in the correct way. You need to see the people who eat this stuff, they almost roll it down. The starch needs some lubrication. The starch itself has to do with the farming communities here. If you are from that, you didn’t eat ’til 6 in the evening. Yams are very, very nutritious – the big hairy ones not the sweet potatoes. They say you have twins because of it.

It’s for fertility?

I don’t know if it splits the foetus or what it does. Alice Walker mentions it in The Colour Purple, there’s child who has sickle cell anaemia and everyone brings her yams. The yams kept us healthy. There is also a connection with malaria, everyone has got it in their system. They are just walking around with it. Someone needs to do the research, to find out the medicinal effect.

Also, you have yam to help with the menopause.

Slimming pills are made from bush mango. It’s mucilage.

So slime is good for you?

My father is a paediatrician, he thinks the reason we are more diabetic is because we are drinking more soft drinks: Coca Cola, Sprite. The recipe is different to what you have, we have more sugar. But in Africa we don’t have food standards agencies saying there is a bit too much sugar here. In your country I find it hard to watch television because every five minutes, there is always something delicious on TV.

Another question I wanted to ask is about palm oil, which is essential to Nigerian cooking. Do you get the palm oil from Nigeria itself?

I try to buy my palm oil from one place. I know this person who makes it with conscience. You can sell it out of a jerry can. The quality control is almost zero on palm oil – that is the number one problem.

Backtrack a little bit. My husband’s grandmother is alive, there’s a story I write about, her husband said she mustn’t come to bed in her nightie, she must come to bed naked. This woman is knocking on 90. Her ankles are this slim. This woman is eating palm oil all the time. They are so healthy. You have to question the propaganda. There’s a big question mark. Like canola (rapeseed) oil, my children ate it, now we aren’t supposed to eat it. My son was told to eat soya, because of all his allergies, because he can’t eat cow’s milk, and it was the worst WORST advice.

I’ve just read Tim Spector’s The Diet Myth and it’s all about gut microbes. We could probably talk for hours about this. Autism is so clearly associated with problems with the gut. Dr Andrew Wakefield was criticised for linking vaccines with autism. I wouldn’t be surprised if he was proved to be right eventually.

If you are a mother, you see the connections. At some point we stopped the vaccines for my son. No one is saying don’t vaccinate your kids. I do it with my daughter. We are told you’ve got to vaccinate your kid. You’ve got to remain vigilant.

I didn’t vaccinate my daughter.

Another of these so called fringe people, a lot of what they are saying is true. In 20 years time, we may be saying oh we are sorry.

So sorry we demonised you, made you lose your livelihood.

For the first 7, 10, 13 years, you’ve got to monitor it. If you lose that time, you end up with a severely disabled adult. There’s nothing you can do about it.

I spoke to another mother in Britain who has two autistic sons. She makes raw fermented sauerkraut, which she injects into their mouths every day.

The child will never be neurotypical. You want a functioning child. My son is allergic to cabbage, so sauerkraut is out of the question. The gut is an individual, the biome. You don’t want to eat meat, I actually enjoy my meat, we can’t exchange stomachs.

It’s different for everybody. I’m gonna get my poo analysed. This guy Tim Spector runs The British gut project.

You have to send your poo?

I’m not sure how they do the stool sample.

There must be an easier way.

Also Maggi sauce, stock cubes? It’s become an intrinsic part of African cooking.

Yes, it has. It’s got to the point that every stock cube is now called Maggi.

It’s just a shortcut to get that umami flavour.

Only if you don’t know what the real stuff tastes like. It shouts. I know I spend a lot of money on electricity here because I’m always roasting something. I can’t even imagine going back. It forced me to go and look for good salt. I’m glad we can’t eat it. Not at all. I don’t use Maggi at all. Not even Thai fish sauce. I use nothing with monosodium glutamate.

Are you careful because of your son’s issues? You are more careful about what you put in the family diet?

Absolutely. I wouldn’t cook every day if we didn’t have this thing which we have to get done. It’s a commitment. If it wasn’t for my son, I wouldn’t have written Longthroat Memoirs.

That’s interesting because a food blogger I interviewed, Papilles Pupilles, became a food writer because of her children’s food allergies.

I don’t think we know much about African food in the West. There must be so many ingredients we know nothing about. We are getting some like baobab seeds. In Botswana they eat water lily bulbs. And you are part of that. It’s almost an hierarchical attitude towards food, French is at the top…

And we are at the bottom. (Laughs.) I don’t think there’s anything you can do about that. In a sense, I don’t mind…

What do you think we should discover in African food, what should we know about?

I think we should break it down. I don’t even know what they eat in Cameroon. They have lots of spices – njangsang. They have a country onion I’ve never even heard of. You can’t say Africa. It’s each individual country, the diversity is amazing.

I’m thinking of, say, South America; how the food has spread. Nowadays everyone eats ceviche, which nobody ate ten years ago.

I’m thinking jollof rice. There’s Senagalese jollof rice, Ghanian jollof rice.

I’m going to do the recipe in your book. But what is a ‘tatase’ pepper, which is mentioned as an ingredient?

It’s not a bell pepper. It’s got a lot more heat. It’s not sweet. Use the look, they are long. You need a large mild chilli. Like really large jalapenos. But not too hot. Have you tried Peckham Rye market? I had people calling out Shaki shaki. Obviously I look Nigerian.

What is Shaki shaki?

It’s tripe. You may find the right peppers in Peckham. This was a South Asian person shouting shaki at me.

I do love London for that. We’ve got everything here.

What ingredients should we know about?

Jamie Oliver used Nsala spices. There’s a recipe for it, there’s a pod which we use to make Suya, it’s like barbecued meat but better than that.

Nsala is made of several spices: black pepper, different kinds of peppers, with different aromatics. Cubeb, long pepper, grains of paradise, hot peppers without the seeds. The recipe is in the book.

That sounds a really good thing I could try.

Talking about authentic foods from countries prior to new world ingredients… Nigerian food has Scotch bonnet peppers, but that’s new.

Even the rice. We grow rice, it looks very different from imported rice. I don’t think we were eating rice. People cannot digest it. I think that’s actually a good indicator as well. I don’t know anyone who has a yam allergy or who can’t eat palm oil. Cows milk for instance, southerners can’t digest it. Northerners can, but they drink it raw. There’s just a lot that has happened.

Raw milk is really good for your microbiomes in your stomach.

I don’t have the courage to do it, but I hear you can digest the raw better.

It’s interesting about cultural heritage and food. The relationship of African food to slave food in America, New Orleans gumbo and all that. For instance in Grenada they called it provisions, things like yam are provisions, slaves had their own little poor territory gardens where they’d grow their little provisions. In a sense, African food has travelled and become Southern food in America.

Yes, think of akara, beans that have been fried. You can find that in Cuba. The name akara is Yoruba. It’s the same food they use over there, it’s the same food, but it’s travelled.

When I came to London, and not being able to wrap my palate around the food, it was quite traumatic. We’d go to Brixton and Peckham and buy okras. Even the texture of chicken, the texture of meat. We like our meat tough. The tougher meat is the one that is more expensive. We were shocked to find out mutton is cheaper than lamb.

Thank you so much Yemisi, it’s been really great to talk to you.

Longthroast Memoirs won the John Avery Award at the Andre Simon Book Awards last night.

Buy Longthroat memoirs here.

On Twitter: @yemisAA

On Facebook: Yemisi’s Longthroat memoirs

Website (under construction): Longthroat Memoirs.

Hi Yemisi and Kirsten! Great article, I really enjoyed your conversation! Now time to get the book!