Within an hour of arriving in Bundoran, I tentatively type the word into Google. It auto-completed with the words ‘is a shithole’.

We planned this trip pre-pandemic. Two years later, I’m here with my mum, dad and sister. We are trying to find out more about the ancestral Irish side of our family. My great grandfather, Mick Rodgers, was born in Bundoran, near Ballyshannon, and moved to Glasgow where he met Isabella Anderson, my great grandmother. She was already married with kids but declared she hadn’t seen her previous husband for eight years while he was out fighting World War One. Isabella came from a fishing village, Arbroath, in Scotland, which I visited last year. She started out as a hemp weaver. Mick and Isabella had two kids together out of wedlock: my grandparent John Harris Rodgers and his sister, another Nora.

Day One

It’s all different going to Eire since Brexit. It’s always been expensive and now it’s even more so for the British. It doesn’t help that Three, my mobile network, forced me off my long-standing rolling contract last week and is now charging some horrendous amount of money daily, to get roaming in Ireland. Cunts.

Then the car rental company, Sixt, charged us £48 to cross the border. There is a strip of land, approximately nine miles wide between Northern Ireland and Eire. So it cost £48 to drive nine miles. Sucks.

From Belfast airport, I drove past a ‘proddie’ estate. You can tell because the houses are all new red brick and covered with British flags.

It took hours to drive to Donegal. My dad, who is now 86, can no longer get car rental or insurance. Did you know that after the age of 75 it’s virtually impossible to hire a car? Life and travel gets very restricted, very expensive. So I drove and he navigated, something he is spectacularly bad at because somehow his fingers don’t properly work on an iPhone. Maybe he touches too hard or too soft or his fingers are too dry, I don’t know. He’s on Apple maps rather than Google maps and can’t cope. He designates himself the grand title ‘Master Pathfinder’ but can’t navigate for shit.

We pass villages and rolling countryside: deep green fields, sheep and cows, new breeze-block bungalows, dark skies and sunshine. I see flags with William of Orange on them. I think we are in Orange March territory. I once covered the Orange Marches in Portadown, back in the ’80s. Terrifying.

Finally, nine miles from the sea, we cross a bridge. We see bureaux de change, the signs change into kms rather than miles, and everything is now in Irish and English. I get a text from Three saying you must now pay an extra £5 a day.

Bundoran is a seaside town. On first sight it looks like a dump. The Airbnb looks like Irish council flats. The inside isn’t too bad; as if Changing Rooms has tried to do a beach-style makeover consisting of a few planks from a pallet, rather than actual driftwood, nailed into a wall, underneath a cheesy sunset beach photo in a plastic frame.

The apartment manager warns: ‘Don’t go into any of the Celtic pubs, they are heavily republican. I’ve lived here 10 years and I’ve never been into them.’ I laugh. He doesn’t, he’s not joking. There is a big fun fair on the beach pounding out awful music. Hardly the windswept romantic destination I’d imagined when we booked.

Dad goes for a walk. ‘The beach is nice white sand,’ he reports hopefully. Sis goes to the shops. ‘Every restaurant serves chicken goujons,’ she pauses. ‘The Indian restaurant serves spicy chicken goujons.’ She buys a family pack of Taytos at Lidl. ‘They only have cheese and onion flavour.’

I check my phone. Top story on Irish Twitter: ‘Woman who lives on crisp sandwiches for 23 years is diagnosed with serious disease.’

I go to bed early.

Day Two

Went to Bundoran tourist office. ‘What do you recommend here?’ we asked the pink-haired lady working there. ‘I recommend that you leave and go somewhere else like Killybegs and don’t come back.’ (Somebody later told us she was joking – ‘that’s just her way’ – but we couldn’t tell.)

I drive to Killybegs, passing through Donegal Town. We pass the ‘diamond’, which means marketplace. Killybegs is a sweet fishing town with good restaurants.

Anderson’s boat house isn’t open until 3pm. ‘It’s because his wife is working in the Seafood shack on the front until then,’ someone informs us. I see a sea facing pub serving Killybegs ‘Number 1 Guinness’. A red-haired family sit outside. Everybody says hello.

My sister buys calamari and haddock goujons at the Fish Shack. We return to the pub to drink Guinness. Inside children are playing pool and men are propping up the bar. A red-haired bar lady asks me: ‘Are you gentlemen or ladies?’

‘Three ladies, one gentleman,’ I reply.

She slowly draws four Guinnesses; one in a straight glass, the other three in ladies’ glasses. The football is on, green flags and sporting T-shirts line the walls. Ships glint from bevelled glass.

There is a local craft shop, which sells books and blankets. At 3pm, we eat at Anderson’s. Delicious fish chowder with sweet brown malt bread and butter.

Driving through Ballyshannon on the way back, where my great-grandfather Michael Rodgers was born. It looks poor. It has a ‘department store’ Slevins selling dresses branded ‘Pippa and Kate’. Down a lane there are pubs and drinking establishments dated from the 18th century. Michael must have drunk there. There is a workhouse and a memorial to the famine.

My dad discovers an island, Tory island, with a population of 190. The king is a Rodgers but he died and there is a vacancy. I want to go. You have to greet everyone that arrives off the ferry and they buy you a drink.

I vaguely remember that Aran island is where some ancestors come from and it’s nearby. The Irish Aran is the one famous for the cable knitwear, not the Scottish Arran.

Day Three

We went to Sligo where we investigated Michael and John Rodgers. We found John’s marriage certificate to Nora. Sligo is pretty, with vintage shop fronts and a marvellous wool shop. The salesman charms us into buying socks and slippers and baby clothes. I wanted to buy a sweater but the width seems to be restricted to the size of the loom. Sizes small, medium and large get longer but never wider. I always need wider.

On the way back, we drive through Mullaghmore, where Lord Mountbatten was blown up in a fishing boat, along with his twin son and a local boy, by the IRA. It’s idyllic. We book for Friday at a local restaurant Eithna’s by the sea.

My great-great-grandfather John Rodgers was a postman in Tullaghan, a beautiful coastal village not far from Bundoran. Across the sea, we see a rainbow and imagine a pot of gold and leprechauns dancing at the end of it. We try to guess what cottage he lived in.

Back in Bundoran, we eat really fresh fish with buttery vegetables at Maddens Bridge Bar. I’m agreeably impressed by Irish food: it’s local, natural and simple.

My sister and I walk around the headland, visiting the fairy bridges, carved out of the cliffs by the Atlantic. It’s sunset, in fact it’s only really gets dark by 11pm. Despite my initial opinion, I’m starting to fall in love with Bundoran. I’m often grumpy and negative the first day of travel.

Day Four

I drive to Tullaghan to visit the petrol station, which everyone says is owned by a Rodgers. I introduce myself to the daughter who is working at the deli counter with a remarkable range of ‘breakfast rolls’ and she yells for her dad.

We sit down and tell our story, our quest. ‘I’m enjoying listening to your story, and I’m not going to stop you, but we aren’t related,’ daddy Rodgers tells us.

One of the questions I ask all the Rodgers I meet – and there are a lot of them around these parts – is ‘are you with a d?’. The petrol station Rodgers are sometimes with a ‘d’ but when they go back to Belfast they lose the ‘d’.

He tells us to go opposite to call on Pauline Rodgers. My dad and I are both nervous of dogs. There is a guard dog. We approach the driveway with trepidation. My dad gingerly puts out a hand to stroke the dog who immediately turns his neck in pleasure. The dog is more interested in barking at cars.

I knock on the door. Nobody answers. I push the door handle wondering if the doorbell proper is inside the porch, but the door is unlocked and opens wide. The dog casually strolls inside. Dad and I look at each other.

Then an understandably annoyed-looking woman comes down with a towel on her head, dripping. ‘What’s all this commotion? I was in the shower!’

I apologise and explain our reasons for being there.

‘Did that dog bark at you or guard the house at all?’ she asked.

‘Er, nope,’ we reply.

We get chatting.

‘Are you with a ‘d’?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’ll ask my Jimmy, he’s done some work on this,’ Pauline says. ‘But I think you may be related to the Tawley Rodgers.’

The Tawley Rodgers somehow sound like a far-away sect, but it turns out Tawley is about two kilometres away.

Pauline is very helpful and asks for my dad’s telephone number: ‘I’ll give you a dingle tonight.’ A phrase that has now passed into family lore.

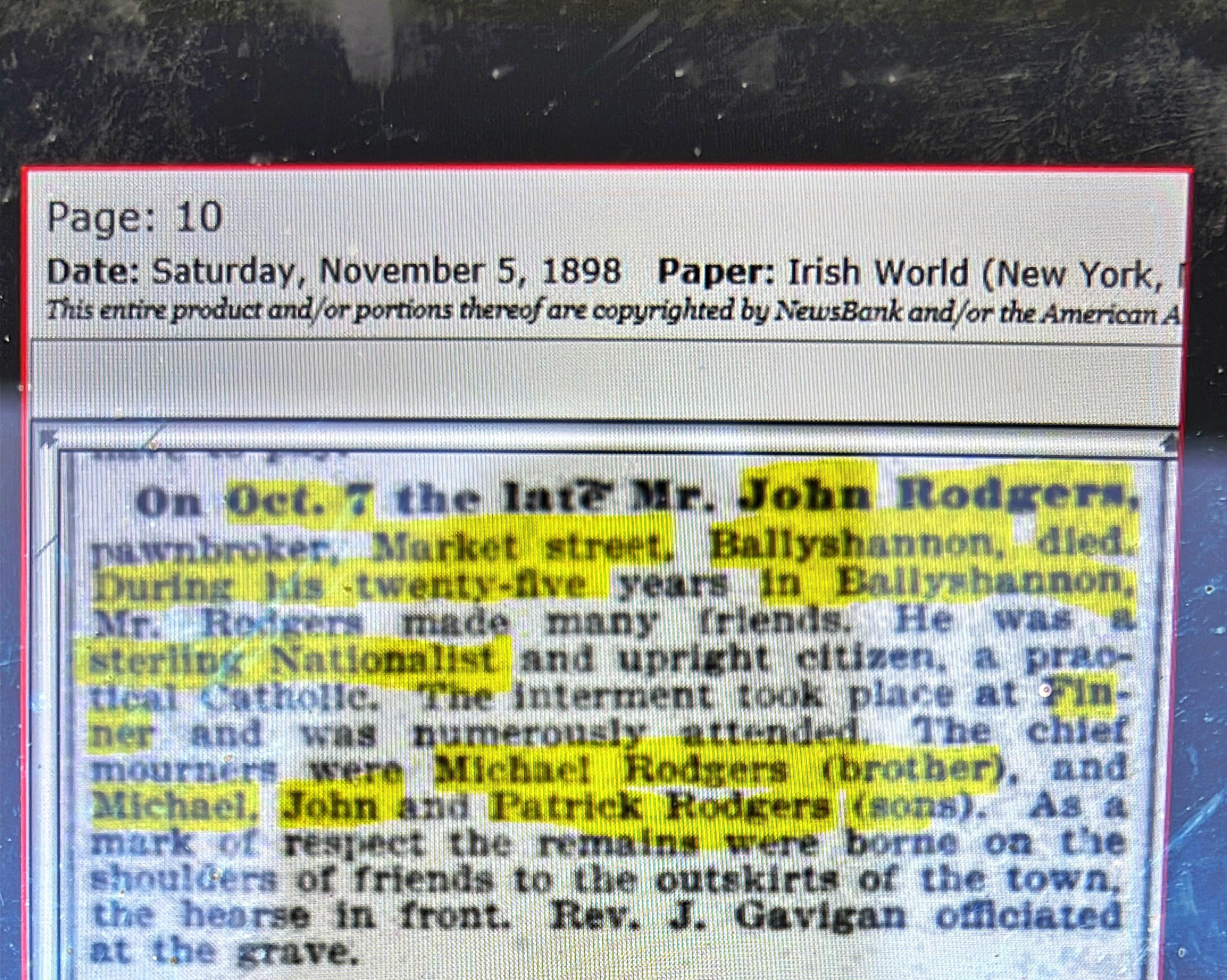

We’ve found a notice in a New York Irish newspaper about the death of my great-great-grandfather John Rodgers. The funeral took place in Ballyshannon and they walked with the coffin (they must have had a cart) to the graveyard at Finner, just before Bundoran, about nine kms. After Nora’s death, which we cannot find a certificate for, he married another woman, Susan Tunney. That’s why two of the sons (John and Michael) got pissed off and moved to Glasgow, leaving, we think, only a Patrick (brother or son?) in the area and some sisters, perhaps an Elizabeth who was a witness on the marriage certificate. Within a year of his second marriage, he was dead.

John had a varied career, for he could read and write (something noted on the census). After postmastering, he became a tailor, then a pawnbroker. We think he had a drink problem too. ‘Runs in the family,’ quips my sister.

John was a republican and a staunch Catholic. This strip of land between Northern Ireland and Eire is very republican and traditionally Gaelic speaking. It’s the pinch point of conflict. Donegal isn’t particularly touristy, which is a shame because it’s wild soft country and craggy sandy beaches.

The graveyard should be where John is buried and possibly Nora too but we can’t find the headstones. We visit the local priest Munster three times to find out if he has a map of the graveyard but he’s always out. Locals mutter about him. ‘Money Munster we call him,’ says one. ‘He likes a silent collection. No tinkle of coins, he prefers notes.’

‘He’s not that helpful,’ I keep hearing.

Last year when I visited Arbroath and St Vigeans in Scotland, I saw the fragility of gravestones. The information on them doesn’t last long, despite being engraved into stone. Even 40-year-old gravestones from the 1980s are showing signs of wear. It’s not surprising we cannot find the headstones of John and Nora.

Next I drive to Kinlough, where John Rodgers married Nora McMorrow at St Aiden’s church. We see the name of the priest who married them on a wooden board in the church in 1872. My dad phones the current priest. One of the problems is that this area is located on the crossroads of several regions: Sligo, County Leitrim and Donegal. Records are kept locally in Ireland. Most records are held by the parish and haven’t been uploaded to the internet. During the uprising in the 1920s, many records were burnt, deliberately destroyed, to prevent the British having intelligence on the local population and vice versa.

Day Five

We are taken to Simpson’s supermarket where Ann Rodgers used to work. She’s not there anymore but I notice they have a good selection of Irish baked goods such as ‘blaas’, potato scones, and soda bread.

Standing in the rain in her porch, we knock on Ann’s door.

‘Is it that Pauline who sent you here?’ she squints at us suspiciously.

‘Yes,’ I blurt. My dad frowns. I wasn’t supposed to say. I get the feeling that Pauline and Ann aren’t on speakers.

Ann mentions the ‘Tawley Rodgers’ and the ‘Mass Rock’. We resolve to visit there.

- Rory Gallagher statue, Ballyshannon

- Ballyshannon pub

Day Six

This weekend – the weekend of our Queen’s Platinum Jubilee – is coincidentally the Rory Gallagher Festival in Ballyshannon, which we discover is the oldest town in Ireland.

There is a statue of Rory Gallagher, who was big in the ’70s, playing his guitar in the ‘diamond’, or main square. He died of liver failure. ‘He liked a drink,’ said a biography. At the end he was embittered by the lack of attention from the music press and the fact U2 had made it big in America. I don’t blame him. As a punk I was a complete snob about long-haired progressive rock type musicians like him. When you are young and callow, you never think about the feelings of the last discarded pop trend.

My sister spends €80 on a selection of Irish vintage clothes at Rosie Lee’s pop-up shop. When we get home, she dresses up in a plastic ‘leather’ sheepskin lined zippered mini dress, a floppy hat and a shaggy fur coat. I can’t decide whether she looks like a heavy-metal shepherdess, Johnny Depp or a Rory Gallagher groupie.

In Ballyshannon there is a small street that has been blocked off for Rory Tributes. We order Guinness and listen to hard rock with a tinge of Irish folk diddyness.

‘So this is where all the appropriate age men are,’ remarks my sister. ‘It’s wall-to-wall cock.’ And it’s true: I’ve never seen so many middle-aged seemingly single men. ‘They’ve probably got wives at home,’ she says ruefully.

But we have a great laugh mucking about, dancing, listening to the music. Every pub is packed and everybody is friendly. People come from all over the world to this festival.

In the light evening, my sister and I strip off and swim naked in the sea. It’s not even cold. My dad looks anxious sitting on the rocks while I swim out into the ocean.

Day Seven

Mass Rock, Tawley

We return to Ballyshannon to visit the Orphan Girl’s Famine Memorial, which is touchingly simple; a large empty stockpot and girl’s names on bricks around it. They were sent to Australia with two dresses and seven petticoats, a sea-chest and a bible.

The workhouse is in terrible disrepair, filled with ivy. It’s actually an elegant building. They need funds to restore it.

On our last afternoon, we drive around Tawley, looking for the Tawley Rodgers and the Mass Rock. A Mass Rock is a secret altar where a stone taken from a church is made into an altar, during times when Catholics were not allowed to worship. This one was in a forest: three stones, a flat one in the middle as the altar, a baptismal font made from a hollowed out rock and another forming the trinity, were placed under the arms of a huge tree. It felt very spiritual and sacred, pagan even.

We knocked on the doors of beautiful cottages down lanes of tall hedgerows and walls tumbling with wild flowers. We asked about the Tawley Rodgers. The twins Shane and Seamus had died but there are some sisters about. Alas we could not find them.

My ancestors got to look at this view every day.

Our last meal was at a restaurant I recommend to everyone, Eithna’s by the sea, run by Eithna herself. She’s designed an interesting menu using local ingredients: my mum had a hot garlic butter lobster Thermidor half, my sister a whole sea bream, and my dad and I with polenta-coated fish and chips. There was a Nori chocolate meringue for dessert, which I will attempt to recreate. Eithna has only just opened up again after Covid.

Genealogy-based travel gives the researcher a goal and an excuse to talk to locals. It includes a lot of fruitless searching around graveyards and door-knocking but is fun. I like to soak up the atmosphere, imagine my ancestors living their lives, smell the air, sniff the wind. It’s frustrating too: the dead ends; the fact that everyone has the same name and were known by their nicknames at the time. Months spent on Ancestry and My Heritage taught me that families fall out and never see each other again. That women did have kids out of wedlock. That several siblings with the same first name were often ‘replacements’ for a child that had died.

My takeaway from this trip is how similar the background of my great-grandfather and great-grandmother were: they both came from wild and beautiful coastal villages, in Ireland and Scotland. Economics and politics determine where we end up. War and famine have pushed my family from the sea to the city. We Rodgers went from Ireland to Scotland to London. My next trip, later this month, is to another sea side village, Minori near Naples, where my Italian side lived. I consider myself a Londoner but I have always been drawn to the sea.

You brightened my otherwise mundane Monday morning up. Everything you wrote, rang true, especially the first day, every single time I go to Ireland I want to just turn around go back to the airport and get back to London. I seem to be tearing my hair out with frustration and banging my head against a wall. Its never straight forward or simple. By the end of the trip, there is part of me that does not want to leave, you start to question city life, I’m regarded as quirky, and I think sometimes living in a city we conform more and forget this. A few days back in Ireland and its all ok, your back to being you.

Don’t you ever change and I will be looking up the Rory Gallagher festival for next year, make no mistake!

Thanks Lynn. It was weird, from shithole to I want to live here forever within about 3 days!

I loved this piece. I really enjoy your writing, and often read it out to my partner. We are going to visit Northern Ireland next month for the first time. I have high hopes for how I’ll feel, being there. I’m mighty fed-up with Scotland and it’s politics just now. I have an English mother, Scottish father, was born and brought-up in the South East of England, but have lived in Scotland for 38 years, and the atmosphere here is very anti-English. My daughter is looking forward to finding out more about her Irish ancestry on her Dad’s side. Keep posting.

Thank you so much Karen, this means a lot to me. The thing is, the English are Scottish and Irish and Welsh. We are a mixed bunch. The anti-English thing is awful. The apartment manager in Bundoran said ‘It’s not English against Irish, it’s rich against poor. Rich Irish behaved just as badly towards the poor as the rich English’.