From the moment I arrived in my tiny car with catering tins of coconut milk and tomatoes and 100 kilos of donated Shipton Mill flour, slumped like lumpen bodies in the boot, the Refugee Community Kitchen in Calais reminded me of my activist past, of squat cafes, of cooking at festivals.

Young people with dreadlocks, fresh faced students, punctuated by the odd older person were basking in the May sunshine, eating a simple lunch of lentils and salad.

I off-loaded my food supplies, a young Australian woman noting with concern that they only have one week of rice left.

‘We are desperate for donations. Usually there is a line of vehicles waiting to deliver, but today we only have three: you are the third.’

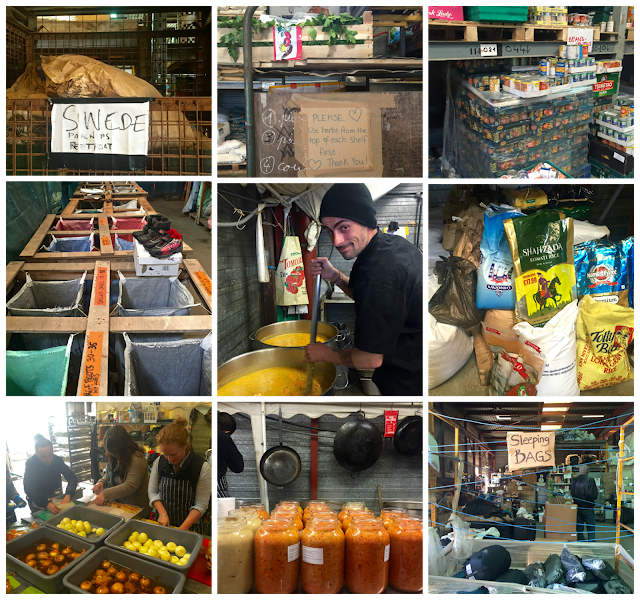

In the kitchen, set in a tented section with low burners lining one wall crowned by enormous hundred litre stewpots, I suggested I could make flatbreads with the flour. The kitchen comprises several stainless steel counters, an industrial mixer, a robo-coupe, hot water and a slightly dodgy oven.

The stores are well organised with sections for dry goods, tins, spices, fresh vegetables, herbs, and an area where they bag up family packs so that some refugees can cook for themselves.

Further along the vast warehouse is where the clothes and bedding are stored. First they are cleaned then sorted into types of garment – hoodies, men’s trousers, womens t-shirts long-sleeved, etc. There is a large area for sorting shoes into sizes; one woman volunteer checks their laces – are they matched? Are they in good condition?

At the back are shelves full of water bottles, camping stoves, saucepans, plates, cutlery, childrens’ toys.

If you volunteer for the kitchen you will be catering for around 1,500 people a day. Usually three pots (300 litres) are for stew, all made with the same aromatics – 1 part ginger, 1 part garlic to 2 parts onion.

Paul, the head chef, has perfected the art of making perfectly fluffy rice, 500 litres, for 1,500 people. This requires experience and know-how. Their technique is to ‘dress’ the rice with oil then parboil it, scoop it into gastros (the metal rectangular pans used in catering) and let it continue to steam, adding nuts, sultanas, spices, fresh coriander.

‘This is basically Ready Steady Cook en masse,’ explains Paul. ‘We use one tonne of food per day.’

Always there is a curry or stew, rice and salad. The refugees LOVE salad. I can see why: when you are camping for months on end without running water, you end up craving raw vegetables.

Simone, who used to be a singer and is now the kitchen coordinator, tells me:

‘Some chefs get here and want to do complicated dishes, say fennel, ginger and orange salad. But actually the refugees want simple food: lettuce, cucumber and tomatoes.’

At the moment there is a surfeit of swedes. The trouble is the refugees don’t like swedes, finding them too sweet. The idea of sweet vegetables in curry is anathema to them. They aren’t mad on courgettes either.

Another chef tells me: ‘The Africans don’t like salt, other nationalities love salt. Some of them love spicy food, others don’t. Surprisingly they don’t really like Indian food…’ (implying there is a kind of snobbery about it)

It’s difficult to cater for everyone. Some of the chefs are professional, but this is mass catering, a different ball game. Viv, for instance, who has worked for Deliciously Ella and The Detox Kitchen, volunteers one week a month, depending on how much paid work she has.

All sorts are providing supplies: Riverford Organics sends vegetables by the tonne. Welsh vegetarian organisation The Parsnipship regularly bring over produce. Sometimes individuals drive up with just a few items. The day I was there, dozens of five litre glass jars of red pepper sauce and babaghanoush from Ottolenghi were being added to a curry.

‘This week Ottolenghi saved our arse, we’ve so few donations.’

Lush cosmetics gave £53k to build the warehouse.

‘Pretty good considering they get no advertising from it. They gave us cash, not products.’

‘We have the best smelling refugees in the world,’ joked Paul.

Later we visit the infamous Calais ‘Jungle’. There are myriad rules. Don’t go at night. Wear baggy clothes. Don’t give any personal details. Don’t ask their stories, you might trigger bad memories.

I leave my car outside the camp.

‘Have you got anything valuable in there?’

‘Yes I’ve got my laptop.’ (I hadn’t yet checked into my hotel.)

‘Hmm. You might be ok as there are police around.’

This place is full of rats at night.

‘I thought they were rabbits,’ says Viv. ‘There were hundreds.’

During my entire three day visit I only see four female refugees. Paul, the Scottish chef who is a long term volunteer, talks about the hidden women:

‘We mustn’t judge their culture.’

Behind me, my daughter fumes, remarking later that he is a mansplaining brocialist.

Walking down the ‘high street’ of The Jungle, there are two bakeries, a barbers, a bookshop, several grocers (packs of ten cigarettes wrapped in silver foil) standing in front of neat shelves, a few chai shops, some restaurants. I take a picture of the cigarettes.

‘Don’t take pictures,’ says Paul. ‘Things could spark off.’

‘I only took a picture of an object with my iPhone,’ I protest.

‘Yeah, well, it’s really delicate.’

I take pictures of things and ask people if it’s ok. It’s always ok. In fact, some people want selfies. They love that I’m with my daughter. Normality. Families. They ask Paul why he isn’t married, why he doesn’t have children when he’s in his 30s.

At one chai shop, the edges of the room covered with billowing rose-blotched fabric, men sprawl and smoke as the sun filters dustily through the gaps in the tarp.

Under the bar are pinned photos of successful emigrés to the UK, each has a date below, the date that they managed to get over the water. 30/11/15. 2/1/16.

‘It’s like tombstones but instead of the date of death, the date is when their life begins,’ I try to explain to one.

He understands and he laughs, translating for his friends. They nod. These are the success stories – those who have made it through the fence, through the tunnel, over and under the English channel to the chalky cliffs and beyond.

Sweet milky chai is offered, a toot of a fruit shisha pipe.

I look at some pencil drawings on a wall. A man sidles up to me and lisps in a whisper:

‘Can you help me? Ten euros please.’

I say no, shaking my head and smiling. If I start giving money, it may never end. It’s hard to know what to do.

Further along we stop to eat at the Three Idiots restaurant where the charming restaurateur, a Pakistani who learnt good English in Israel, welcomes us.

‘Please please welcome. Remove your shoes,’ he beckons, bowing, for us to ascend a small platform built around the edge of the space.

We eat cross legged around a piece of coloured plastic tablecloth, used as a picnic blanket. Vegetable samosas, spinach, lentils, rice with sweet carrot batons and raisins cost us eight euros. The food is very good, as is the nearby bakery that sells freshly made naan bread in a fiery tandoor oven. I start to feel embarrassed that us Westerners are cooking for them when these people cook so well.

‘Why am I making bread when they make fantastic bread here?’ I ask a volunteer.

‘Many refugees cannot afford to buy the naan.’

It costs one euro for three naan.

In this camp there are 5,000 souls sometimes sleeping 12 to a tarped-up hut, and I’ve heard claims that there are 1,000 women but I don’t see one in The Jungle, not even one.

The men try every night to get on lorries, to make it to England. Some have got through and manage a couple of years before getting deported back to their countries. Then they go through the whole process again, making the gruelling journey to Calais. Sometimes, those that do reach the UK miss The Jungle. It’s a community. Starting from scratch in a new country with no money, no accommodation, no job, no family, hiding from immigration, must be very lonely. When somebody gets asylum, there are celebrations in the camp.

As you drive from the ferry port you can see patched up areas in the white metal grills, topped with the rolling coils of barbed wire, where it has been cut. The camp is very near to the port, a tall fence, a sand bar, tufts of long grass and then the tented shacks, strapped like badly wrapped presents, tarp blowing in the beach winds. I imagine the atmosphere was very different through the long winter.

Right now lots of people are getting through to England because many French police have been deployed elsewhere in France to deal with riots.

I ponder the refugees I have met. The energy they must use up. The determination. I don’t know how they keep going.

‘Why the UK?’ I ask a volunteer youth worker.

‘It’s the land of milk and honey. We have benefits, we aren’t as openly racist as the French. They’ve been treated horribly by the French. And we speak English, plus there are already Afghani, Pakistani, Syrian communities in the UK.’

I meet a Belgian guy who gives slam poetry workshops. I think, but don’t say, that this probably isn’t a very useful skill for the British economy, but at least it keeps them entertained.

Perhaps they have a distorted view of the British people via the volunteers. We are all smiley and friendly and non-judgmental: the volunteer men are dispensing ‘salam alaikums’, back slaps and hugs. Many long term volunteers are judgmental of other ‘lesser’ volunteers, who they refer to as ‘voluntourists’. There’s always a hierarchy, the cool kids versus the rest, even in the most well intentioned organisation.

One young woman half my age tells me my footwear isn’t adequate (it was), my apron shouldn’t be worn to the camp (why?), if I put my bag down it will be treated as a donation (useful), that my cookbook will get splashed (so what?). I felt like I was treading on eggshells, everything I did was wrong.

There is the beautiful Israeli girl who speaks Urdu who gets told off for inadvertently showing her bum cleavage in one of the cafes.

I ask some heavily made-up peroxide blonde girls with blue face paint on their cheeks (yes, they seem to think they are at a festival) if I can take a picture of their meal.

‘Only the food, not us,’ they sniff.

‘Oh because you are illegal immigrants,’ I say sarcastically.

What the refugees are seeing actually is British hippiedom in full flow. This is not England. This is alternative England, the England of Glasto and protest marches. Things will be very different if they succeed in getting here.

On the second day I make 300 peshwari pitta breads, filled with dessicated coconut, sultanas and ground almonds. The oven doesn’t work so I cook them on flat pans on the low burners. By the end, my daughter and I are like a well oiled machine, dividing up the dough, weighing it, filling it, rolling it out, toasting it. It’s not enough for everybody as I have to wait until the main food is finished. I feel disheartened but Paul assures me it’ll be a treat for the refugees to have home-baked bread, even if it is just the women and children.

That evening we work till 7pm, clean up the kitchen and go to a restaurant in Calais, the only one open on a Monday night. It’s a fussy looking restaurant with lace curtains, peach tablecloths and empty Balthazars and Jeroboams bottles of champagne lining the stairway. The restaurateur is alone and we are the only customers. We chat in French and I explain that I’m cooking for the refugees. She smiles sadly:

‘No one comes to Calais anymore because of this situation. Les gens fuirent (the people flee). They read about the refugee camps and see it on the news and they are frightened to come. It’s hard to keep the business going,’

Suddenly I see things from their perspective. Calais and the North has always been the poorest part of France, with the highest unemployment and alcoholism.

We eat our set menu, three courses and two glasses of wine cost 72 euros. The food is refined and well presented. This is the only money she makes all night.

A sleepless night at the F1 hotel (30 euros a night, walls like cardboard) and a decent croissant at a bakery, we drive half an hour to the refugee kitchen.

While waiting to continue with the bread, for a free work counter, I chop vegetables with the other women: tomatoes, aubergines.

We are told that we have been bumped off the distribution rota, the opportunity to serve our food to the refugees in The Jungle, which is disappointing as we are leaving that night.

I drive instead to Dunkirk, which Jeremy Corbyn visited this winter, where they are building a new kitchen. You can see the camp from the autoroute, wooden structures rather than a shanty town of tents and tarps. This new camp is mainly Kurdish and Syrian refugees.

I’m shown to the kitchen where the atmosphere is very different from Calais, welcoming and relaxed. Here the refugees themselves are the chefs and the volunteers do the prepping.

My daughter and I are given name tags by Sylvie, a French volunteer, which is lovely as people can talk to us using our names.

One of the Kurdish chefs, a baker by profession, calls to me:

‘Kerstin, you want to cook tonight? You be the chef!’

‘So sorry I can’t as I have to catch the ferry,’ but I’m pleased to be asked.

We catch the lunch session and are encouraged to help distribute. We stand in the serving van; there is a long queue of around 200 people. The first pot is rice and fried potatoes, the second is a Shlai Patata, a tomato and potato stew with mysterious objects floating around.

‘What is this?’ I ask the chef.

‘Humi,’ I think he replies.

‘Hummus?’ I haven’t understood.

Then I eat a bowl, I’m hungry, and I pull apart the strange black object which turns out to be black dried lime softened in the soup. In fact the chef was saying ‘loomi’. It’s deliciously sour. I’m so nicking this recipe.

The third dish is the salad, a chunky cucumber and tomato salad with lemon and then my breads, which are a mash-up between peshwari naan and pitta breads.

Some refugees just want salad and bread. They look at the sultanas intently. They pick them out, eat them then smile and ask for more. The breads I made that day are still warm.

The atmosphere is jolly with Kurdish music, loud joking, dancing, singing, catch phrases in various languages.

‘No pasa nada’ cries chef Rebar, something he’s learnt from his new BFF, a Spanish guy with whom he plays dominoes after the meal.

Again, the majority are men (some of them, my daughter and I agreed, were rather handsome).

Later we drink tea together, or should I say, we drink sugar with a little tea. At the bottom of the cup I can see a melting mound of ‘white death’. Haval, a Kurd, plays guitar.

Sylvie, a French woman who has been volunteering since December, tells me what they need:

‘We don’t need chefs so much, we need choppers and helpers. We always need help though. Yesterday we had hardly anyone. Here in this kitchen we want the refugees to cook themselves. Originally, Utopia, the organisation here, didn’t want that because it’s a security risk. We give the refugees cards. They all want to be here, they are near the food then.’

I think if I were a refugee, not having control of my food situation would drive me crazy. I hate staying with other people when you feel like you can’t eat what you want. Sylvie continues:

‘We are forming three teams that will alternate. We want one of the teams to be women but we have to get their husbands to agree. The husbands didn’t want them to come because of the German men. We are working on that with the help of a Tunisian volunteer who speaks Arab – she’s talking to the husbands. We’ve said the husbands can come and check, make sure everything is ok.’

In Dunkirk they provide three meals a day:

‘The ‘German Kitchen’ makes the breakfast, fruit, hummus, babaghanoush, every morning. This Kurdish team make dinner every night.’

‘Are you German?’ I ask, as I want a translation.

‘Yes,’ he says, pausing. ‘But I don’t want to be.’

‘Why?’

‘I want to be me, not a German.’

I think of all the young men outside the kitchen in the camp that would love to have a German passport.

The German tells me that when the refugees cook for themselves, the queues are enormous.

‘They know what the camp wants to eat. Their food is very popular.’

‘And it’s really good food! I exclaim. ‘It gives them something useful to do, it’s empowering. ‘

‘Yes, it’s the taste of home. ‘

Sylvie’s List for Dunkirk Kitchen

Fresh herbs, particularly coriander

Natural yoghurt

Chicken (they rarely get meat)

Fresh tomatoes

Cucumber

Vegetables – lots

Fruit – always

Aubergines – they like them

Water

Sugar

Red lentils

Chick peas

Large white beans in tins

Spinach in tins

Green beans in tins

Basmati rice (good quality if possible as it’s easier to cook in bulk)

Flour

Fresh yeast as they like to make bread

Eggs

Milk

Knives for the kitchen (if you volunteer bring your own)

Large catering colanders

Gastros

Chopping boards

Vermicelli

For smaller quantities of food, they put it in the ‘free shop’ for families to take and cook.

Simone’s list for the Refugee Community Kitchen at Calais

Lentils

Spices

Natural Yoghurt

Basmati

Fresh coriander

Onions

Garlic

Oil

Money for gas

Brooms and dustpans

Catering sized clingfilm

Volunteering for the kitchens.

Volunteers, and this is what I did, must pay their own way in terms of transport, accommodation and meals outside of working hours.

Thank you, Kerstin, for this insightful insight.

Thanks Pille xx

Supremely well written and thought provoking Kerstin. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks Helen x

A really interesting article, it's great to see a different perspective. We of course have a lot of refugees here in Germany. Where I live in Berlin, the local school opposite our apartment building houses 150 in their gymnasium. I can't help feeling the lack of personal space and privacy would be one of the hardest parts of being a refugee. The reality of life in Germany is that unless you have a skill that supersedes language (like working for a tech start up) or can work freelance (like me, I work online) then you must learn Deutsch to be employed by a German employer. Honestly the best thing refugees could spend their time in Calais would be language learning (assuming they want to come to Germany).

My husband teaching computer coding to a group of refugees every Sunday. My personal opinion is that it's a program where good intentions have clash with the egos of the founders and also a lack of organisation. This makes it very stressful for both the volunteers and the students.

When I first moved to Berlin I went along to a refugee cooking evening, one by an organisation that has been running them for 2 years. A couple of settled refugees cooked and everyone else (expats) prepped. A group of recently arrived males from the middle east arrived for the meal. I felt bad as they couldn't speak english or deutsch so no one could really talk to them and they just stuck to themselves. I couldn't help feeling that I'd rather give them some money to enjoy a meal out amongst themselves (a normal act of everyday life for most of us) than a big shared meal. I don't know., i probably sound more negative about everything than I mean to. I ran a charity for 7 years back in Australia and have had lots of experiences with volunteering and the community sector and I know how hard everything can be!

The long term volunteers are quite prickly about interactions with the refugees and there is definitely a hierarchy.

I felt that they treated the refugees with exaggerated preciousness but couldn't be bothered to address my daughter by her name or look her in the eye, or talk to her. (She looks much younger than her age but could wipe the floor with them in a political argument). They made assumptions about us.

The refugees are just normal people, not saints, not sinners. They like a laugh, just like everyone else.

gawd it sounds excruciating, how freaking rude!

It was very uncomfortable yes

I was looking forward to this post Kerstin. I myself have been thinking I wanted to go to the refugee camp to volunteer to see first hand what the situation is. There are some positive notes in your article, but for me the fact that woman are hidden away is very distressing and frighting. How can they live in our western society while hiding other people – cos let us not call them woman – away. I can't get over it. I don't care about their culture and their religion, it is 2016 and we can not go back to the days when women were considered property of men. I think some real work needs to be done to talk to these men about what is right and what is wrong. I find that hiding away these refugee women is abusive in this day and age, and it should not be tolerated. Look at it as preparing them for living here in the west. What are they going to do when they arrive in the UK or Germany? Hide the women away and put them on benefits so they can be safely tied to the stove and bed? I like Sienna would have been fuming. How can I respect a man, who does not respect women? I lived in a neighbourhood in Belgium where I was continuously called a whore and other indecent things because I was a Belgian woman and not covering up. I don't want this to become an even bigger problem because refugees aren't prepared for the western world. I want my freedom, our ancestors have fought for our freedom. We have to respect that in our society sacrifice was made for us to be able to lead a normal life, like men.

This is the problem isn't it? Paul said 'we must respect their culture'. And yes, when in their country, I try to respect their culture. But when they are in our countries, they should respect our culture.

Obviously this is an adjustment which will not happen overnight but they are fleeing the chaos in their countries, in part caused by us, and now they need to adapt. It's no point carrying on in the same way in the camps. If they want the upside of our economy, safety and human rights record, they need also to take on board women's equal rights.

It's a very complicated issue.

A friend of mine also volunteered at the Jungle camp. She came away utterly traumatized by the experience.

She told me that the migrants (nearly all male) had the most awful misogynistic attitude towards women that was just unacceptable and disgusting.

She didn't feel safe and it totally changed her mind about the whole thing.

How awful. We didn't have that experience in Dunkirk or Calais but we didn't spend much time with the migrants. Is that why the long term volunteers want to keep people away from the refugees?

Loved reading this Kerstin. Such an insight.

I was just thinking about you this morning Maria. Crazy telepathy! x

Kerstin, please sort this out you and I both know that most of this 'blog' is extrapolated from your own prevolunteering opinions! I and Pol tried extremely hard to make you and Sienna feel welcome.. We even took you out for a meal, we only got monosyllabic replies when we tried to involve you, and you left as soon as you finished eating without even so much as a goodbye! There is a lot of 'fantasy' in this article…. Which unfortunately does not suprise me… If you really have to ask why it's not acceptable to wear an apron for food use in a filthy refugee camp, and get annoyed when we ask you to ask permission to take a photo then that basically says it all. I am in contact with every single volunteer that I have worked with in that kitchen, and I class them as friends.. It is an amazingly positive experience all you have to do is come in without an agenda and you'll love it! Please come out again but this time with an open mind and not for the sole purpose of writing an article… Viv aka weekend warrior (weekend warrior is a term of endearment NOT an insult)!

Hi Viv, first of all I'd like to say you were friendly so thank you for that. You didn't take us out for a meal, nor were we invited actually. I found out about it from a non kitchen volunteer. We paid for ourselves and you all separated yourselves from us. We were not monosyllabic. Anyone that knows me knows that I'm not like that. The only time I grew 'monosyllabic' was at the end when I'd finally had enough of the cold shouldering, the cups of coffee made for everyone else but us, the underlying vibe of irritation. I stopped smiling then and you guys noticed it.

Nevertheless we endeavoured to continue in the spirit of volunteering to help out with the cooking.

I notice that the male chef was taken seriously but I wasn't. I come across this all the time but it was a surprise in an activist community of which I have vast experience. Because I'm a middle aged woman, I felt many of you pre-judged me. I don't look like an activist. But I have been, for decades, and always will be.

I wear an apron all the time. I brought enough clean aprons to change every day, which is what I did. The issue was more that I was constantly assauted with 'advice' as if I were a child.

I did ask permission to take photos, all the time. I'm a professional photographer. But to take a picture of a packet of cigarettes wrapped up unusually and be told off felt over the top.

I didn't come with an agenda.

This piece tries to be as fair and balanced as possible. I salute you all for your hard work. As a writer I have the right to document what I see.

The atmosphere in Dunkirk was non judgmental and cheerful. I'd recommend visiting and seeing the difference.

Kerstin, the male chef happened to be the head chef in the kitchen that week, because all the other chefs were only able to be on site for a few days. The head chef position rotates, and whoever is filling that position in any given week is running the kitchen. The head chef does not deserve to be painted in a bad light because people were listening to him. At dinner when we shuffled down so we could all sit more comfortably – and we asked you to shuffle along with us, you declined, nobody separated from anyone.

It seems a shame that small things were taken personally instead of being talked over.

Glad you enjoyed your few hours in Dunkirk. I split my time between both locations, which is why I was able to introduce you at that site. Both sites/kitchens are fantastic and work together as an extended family to focus on what it is we're all there to do – keep people going with healthy and nutritious food.

The 'male chef' I referred to was the other volunteer chef, not Paul, who I totally understood was running the kitchen and I was ready and willing to do anything he asked.

There is no point you all coming on here and slagging me off and getting personal. I've put the word out about what things are needed. Feel free to write your own blog if you'd like to put your perspective across.

A great insight into a huge, widespread situation. hard to read because you are finally confronted with first hand experience, not something you hear or read on the media.

Thank you PB!

I still would like to volunteer and cook for people who are suffering, whether as a chef or as a helper.

I thought your piece was well balanced. it. mostly concentrates on the food aspect and the rest gives it contextual colour..

Thanks Imogen.

Saw this earnest, hierarchy at Greenham and at the M11 link road protest squats in Wanstead where I once lived, everyone trying to outdo themselves in the right-on stakes and the people with real practical skills get sidelined- or they try to sideline them. It must have really pissed you both off.

And YYY to tghe festival vibe too. What was the volunteer class system like?

In retrospect some of the volunteer class system is due to the age old arrogance of the young who think they know it all! Some of it was due to ingrained unconscious sexism and ageism. Some of it was about the cliquey way that some activists behave, which is great for them but doesn't actually influence anybody outside their own circle.

A very very interesting read, K. Thank you for sharing this.

Thanks Kavey, Sorry it's taken me so long to respond, I think I was a bit shell shocked by the bombardment of comments from people who were angry about this piece, people from the volunteers. I published a couple of them but afterwards I just thought, yeah I guess you are going to take this badly, I'm holding up a mirror to your behaviour and that can't feel good. Hopefully this will give them food for thought.

Thank you for this detailed article on your experience cooking at Calais and Dunkirk! I started the evening researching food bloggers in London, ended with a plan to volunteer 🙂

They always need people. x

Hi Kerstin. Beautifully written piece. Thank you. Some of your experiences chimed with my own. The hierarchies – yes that's familiar. In any group of people I guess it happens. I think it's a legitimate subject to describe. What you've achieved is what my efforts (having followed a similar pattern to you but without the pedigree!) are aimed at – you've encouraged Nancy (above) to volunteer! For that, and for this well observed and wryly funny piece – thank you. julian