American food writing is often more advanced than British food writing. American publishers don’t just support tv chefs, influencers and newspaper columnists either, they push the envelope further. With a larger audience, creative American publishers, such as Abrams and Chronicle, can finance authors who appeal to food geeks like me.

American Food, a not so serious history by Rachel Wharton (Abrams), illustrations by Kimberly Ellen Hall.

An A to Z illustrated book of the history of American foods such as the doughnut, the blueberry, Monterey Jack cheese, velveeta and tomato ketchup amongst others, makes me want to travel to the United States again.

Did you know that Green Goddess dressing didn’t originally have avocado in it and was white with green flecks? I want to go to San Francisco’s Palace hotel, where it was invented, and try the original version. (But on further research, they don’t appear to serve the dressing anymore. Mistake!)

That most American of food products, Heinz Ketchup, is disparaged by gourmets, especially the French, but I love it. But when developing the product, Henry Heinz improved food safety for all American foods.

The authors discuss New Mexican cuisine, pointing out that it isn’t Americanised Mexican food but Native American plus dairy. Likewise ‘queso’, that popular cheesy Chile dip (mentioned so frequently in the movie ‘Boyhood’ which hasn’t yet made inroads into the UK) is Texan Mexican rather than Tex-Mex. Texan Mexican food is the historical food of pre-United States Texas, “whose ancestors are the Native Americans who first lived here over 12,000 years ago”.

Many Italian foods are in fact American by birth, from pizza to pepperoni, the latter distinguishing itself by a smokiness rarely found in Italian food.

There is fascinating research, a few recipes and some necessary myth busting in this small book. Essential reading for any American food fan.

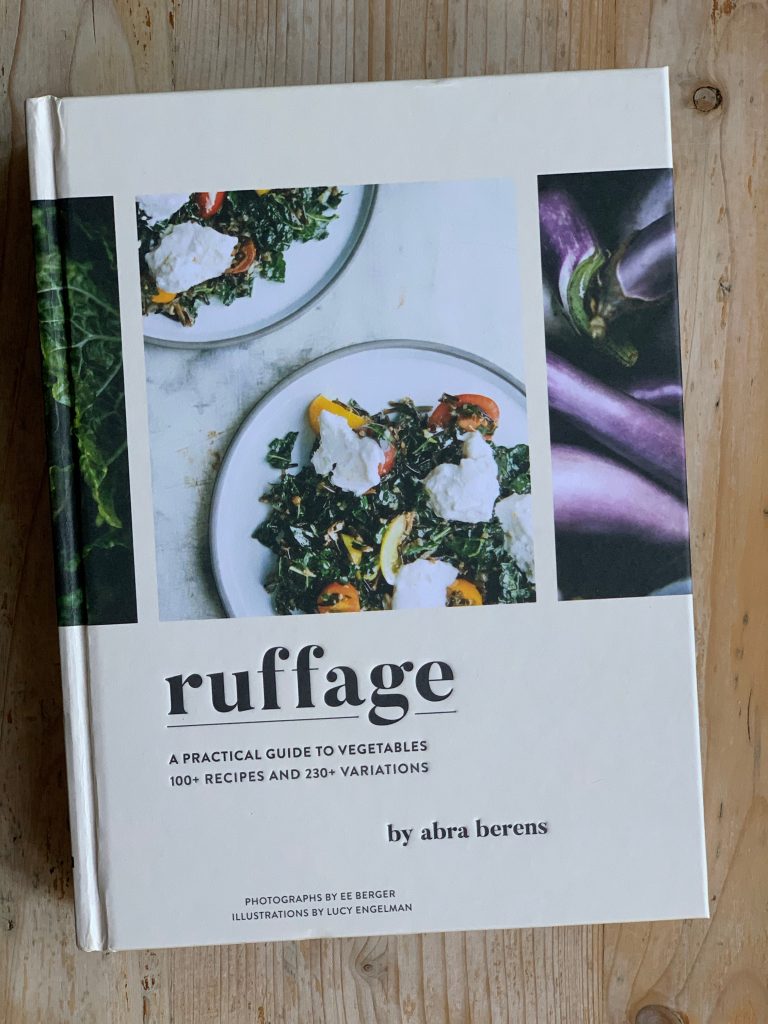

Ruffage by Abra Berens (Chronicle)

Berens was a farmer before she became a chef: “Farming taught me how much freaking work goes into food production, and that wasting food is truly a waste- of money, time and resources.”

The first chapter is about a strong pantry. If I were her editor, I would have cut out much of this. It’s not a book for beginners – we all know how to cook pasta and she’s wrong about the correct rice for risotto. You can tell this is her first book, she wants to explain everything. She has too much to say but writes elegantly:

“A pantry is like a quiver of arrows, at your back and at the ready” she starts, like the Katniss Everdene of cooking. You can tell she’s an outdoors girl.

It’s part two, the majority of the book, that is a delight: like me, she is in love with vegetables and writes about them in tender lovelorn prose. The photographs and illustrations (Lucy Engelman) are beautifully done. Recipes are simple yet sophisticated with several variations. She suggests techniques for preparing and cooking vegetables such as blistering, charring, shaving, massaging and poaching which will inspire.

I believe ‘ruffage’ is the American spelling of ‘roughage’. Eat your fibre people!

Breakfast by Emily Elyse Miller (Phaidon)

To write a book for Phaidon publishers is a privilege, you get a big glossy coffee table tome to add to your CV.

Emily runs an international pop-up ‘BreakfastClub’ (yes one word, a portmanteau of mixed case grooviness). She’s done her research alright.

The largest proportion of the book is devoted to eggs in all their global guises, from the Japanese rolled omelette to Israeli shakshouka, to Eggs Benedict. It may seem odd to have a chapter on soups and stews in a breakfast book, but Asian cultures will often have a noodle soup for breakfast, while India and Northern Africa enjoy a bean stew.

And yes I checked, she does mention Marmite on toast.

If it’s the British fry-up including its ‘magic nine’ ingredients, that interests you, some time ago I did an interview with the witty Seb Emina, author of the Breakfast Bible .

Women on Food by Charlotte Druckman (Abrams)

This large volume is a compendium of female food writing, mostly by Americans but also such UK luminaries as Bee Wilson, Diana Henry and an interview with Nigella Lawson. This is a brilliantly intersectional cast of writers, including black and ethic minority essayists. Anthologist Charlotte Druckman intersperses essays by women working in food (farmers, chefs, writers, home cooks) with round-robin questionnaires: ‘Are there any words or phrases you really wish people would stop using to describe women chefs?’; ‘The truth about my mother(‘s cooking)’; ‘Have you experienced a failing up or a failing down?’ and ‘What are some misconceptions about women who do your job?’. These are all great questions.

Charlotte herself writes a chapter on the ‘catfight’ between two eminent US female restaurant reviewers, Gael Greene and Mimi Sheraton. Their review styles were totally different, (the first wrote ‘features’ and the second wrote ‘service journalism’), and yet, because they are women, they are denigrated by (male) historians of restaurant criticism into being one amorphous girlie type.

This is an American book and so I do not know all the writers. But what applies to the female voice in food in the United States, applies everywhere. The problems and themes are tiresomely recognisable. And that’s worth documenting.

The only clanger is the chapter on horoscopes. While justly remarking that astrology is a devalued ‘housewife’ subject in journalism as food used to be, and that it would likely be colonised by men the minute it becomes important or profitable, the example presented was neither foodie nor astrological. As I’ve worked in both disciplines, it didn’t chime right (the astrology of food is a valid subject and I’ve prepared a menu based on a chart for an early supper club).

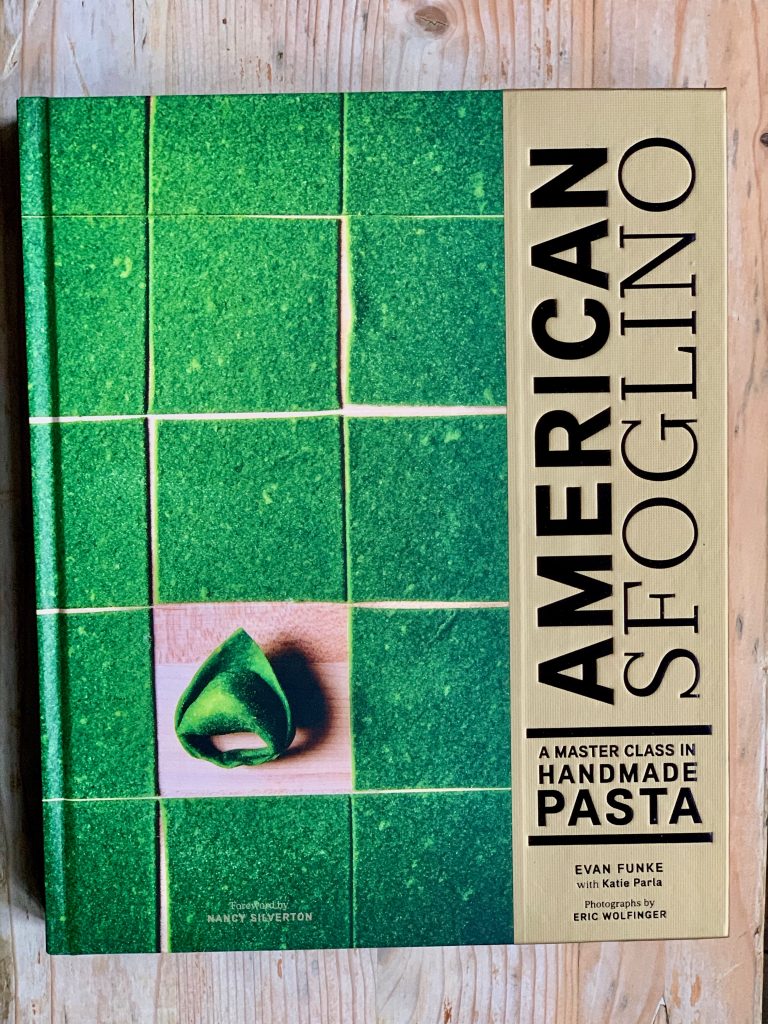

American Sfoglino by Evan Funke (Chronicle)

What is sfoglino? It’s a type of pasta, from the Emilia Romagna region of Italy, rolled out by hand into a large circle. No machine other than a rolling pin is involved. This large book is a masterclass in how to do it. Chef Evan Funke, though an American lacking Italian roots, learnt from two masters, one from Bologna and the other from Japan. He’s a big chap; you can imagine him making short work of a lump of pasta dough, egg yellow and firm, gradually flipping, flouring and flattening it to a fine translucent disc.

The photographs and step by step instructions to different sauces and types of pasta are beautiful and informative. So even if you aren’t likely to make your own sfoglino, it’s an impressive coffee table book for Italian food lovers. I tend to make pasta with a machine, so I’d love to try sfoglino. Why aren’t there restaurants in the UK making it?

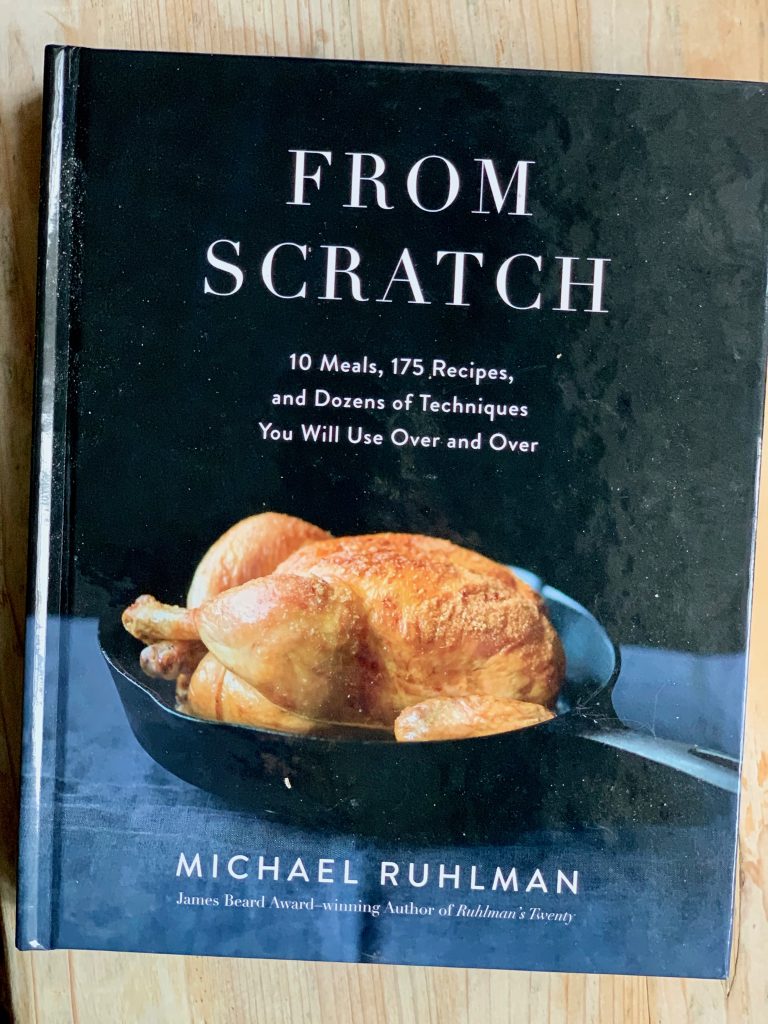

From Scratch by Michael Ruhlman (Abrams)

In American food writing there are two big Mikes: Michael Ruhlman and Michael Pollan. These guys are not only foodies but thinkers; cook -philosophers if you will. Not content with producing another recipe book, Michael Ruhlman is grouping recipes into families and techniques, rather like our own Nikki Segnit in last year’s ‘Lateral Cooking’. They want to get to the essence of cooking methods, the genealogy of recipes.

From Scratch is a big shiny book, with an engaging and approachable voice, taking the reader through ten classic central meals from roast chicken to paella then fanning outwards. Ruhlman starts by asking- what is cooking from scratch? If you are making lasagne for instance, is it making the dish with pasta and two sauces. Is it making the pasta itself and the cheeses? Is it milking the cow/buffalo/goat/sheep then making the cheese, growing the tomatoes and garlic and basil and growing and grinding your own flour for the pasta sheets? How far does this go? How fundamentalist are we being here?

I like to cook from scratch but you have to be realistic. I do have a garden so I can grow some vegetables and fruit and herbs. But it’s hard in any city to keep animals or grow cereals such as wheat. Ruhlman probes this question and gives you options. I’ll be playing in the kitchen with this book all year.

Leave a Reply